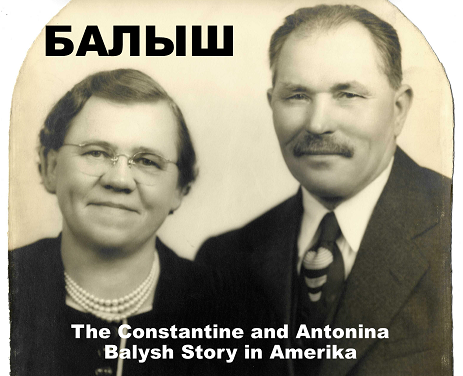

The Constantine and Antonina (Balysh) Balysh story starts with the land, tens and hundreds and thousands of acres of it in what today is known as Belarus. Sometimes claimed by Lithuania or Poland, and at other times existing as White Russia/Byelorussia, it sits north of the Ukraine and west of Russia proper. For most of its history, White Russia was considered backward, producing farm goods and raw materials consumed elsewhere, but without much investment into education or infrastructure.

Our Russian-speaking Balyshes appear to have farmed in this region of the great sweep of the Motherland for generations, dwarfed by the vastness of it all. In his book The Russian Revolution, author Alan Moorehead describes the impact of the physical nature of the country on the human psyche:

… the long dark winter, the spells of intense cold and heat, the vast expanse of flat land that leads on, like the sea, to endlessly receding horizons. A human being is a midget in this boundless landscape. One can sympathize with the Russian’s desperate need to establish his own identity there, his desire, by some outcry, some act of defiance, to reassure himself that he is not nothing in the world.

|

| Constantine's birthplace, Smorgon, White Russia |

That the Balysh roots in this earth ran deep is evidenced by an oft-told story. When Constantine went to marry a girl by the same last name, in a nearby village, they were advised that they were not related. The greater likelihood was that they were distant cousins, and that generations of their ancestors went back so far in time that any memory of a familial connection had been lost. The Balysh children later were simply told that in this part of the world, the name Balysh “was as common as Smith.”

White Russia and Napoleon

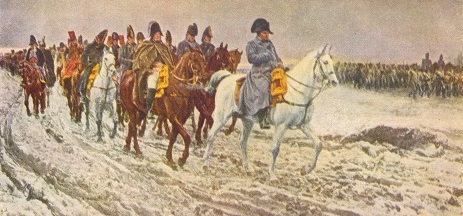

White Russia had gained an infamy many years before, in 1812, during Emperor Napoleon of France’s invasion. Although he pushed deep into the Motherland and eventually occupied Moscow, Napoleon found the great city abandoned, on fire and inhospitable. Ill-prepared for another of the country’s deep, frigid winters, his men lacked proper food and clothing. The historian Charles Alan Fyffe has written that once "the last fires ceased, three-fourths of Moscow lay in ruins. Such was the prize for which Napoleon had sacrificed 200,000 men, and engulfed the weak remnant of his army six hundred miles deep in an enemy's country."

|

| Above: Emperor Napoleon and his army retreating from Moscow, 1812, from a painting by Meissonier. Below: Napoleon abandoning his men at Smorgon, the village where Constantine Balysh would be born 68 years later. From a painting by J. Rosen, |

|

In the face of this defeat, Napoleon decided to retreat. On their catastrophic journey back, tens of thousands of his troops died of cold, exhaustion and starvation in the snow-covered Russian soil. And when word came from Paris that political forces were aligning against him, the once-invincible Napoleon on Dec. 5, 1812 abandoned his men outright and headed home in a horse-drawn sleigh.

The site of this separation was the little hamlet of Smorgon, in White Russia, about halfway between the cities of Minsk and Vilna. It’s the very place where Constantine Balysh would be born 68 years later. Whether or not any of the Balysh forbears were there to witness it can never be known.

Napoleon’s departure is celebrated widely in Russian history as a triumph of nature expelling a parasite when the Russian armies could not. Tolstoy’s great book War and Peace, and Tchaikovsky’s classic symphony The 1812 Overture, are cultural reflections of this era.

The Balyshes in White Russia

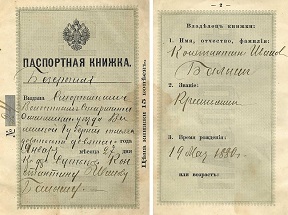

On May 19, 1880, Constantine was born in Smorgon (also spelled “Smorgoni” and “Smarhon”), the son of Ivan and Agnes Balysh. He was said to have been the youngest of 13, although we only know the identities of seven others — Isador “Sedor,” Larry/Leonard/Leon, Wasil/Basil, Paul, Helen Fursa, Frances Cybowsky and Barbara. As a boy, Constantine accompanied his mother, a midwife, on her rounds in the village and received small favors such as breads from her patients.

Russian peasants

The Balyshes were peasants in the Russian tradition as spelled out on Constantine’s passport. They made their lives as poor farmers, and whether they owned land is not known. They gave their allegiances to the Tsar of Russia and to the Russian Orthodox Church.

A few miles to the south of Smorgon, in the village of Sutkovo, Antonina Balysh was born in March 1888, the daughter of Anton and Sophie (Koval) Balysh. Her origins are only a wisp of memory for us, as little of her background is known. She never knew her own precise birthdate in March, it’s said, so in adulthood she selected the 10th for the purpose of official paperwork and birthdays.

Antonina’s father was a blacksmith with a fiery red beard. He was a disciplinarian and never told his children more than once what to do before resorting to the whip. Her siblings were Nikolay “Nicholas” Balysh, Aleksandr Balysh, Kasimir Balysh, Vera Vashkevich, Grigorii “Gregory” Balysh and Ivan Balysh. As the eldest, Antonina grew to womanhood in her parents’ close-knit home. She enjoyed having her mother brush her long, fine hair. She also found pleasure in singing in the church choir with her future niece-by-marriage Anna (Pashkur) Balysh.

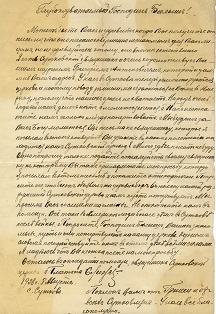

Antonina loved her church, and that devotion later exacted a heavy emotional toll. In the late 1920s, nearly two decades after she had settled in America, when she saw a photograph of the church building badly damaged by German bombs during World War I, and after reading a four-page letter from the church’s priest asking for money to rebuild, she “cried for a week.”

and his wife Martha Razuk

A Look to Amerika

How Constantine and Antonina met is not known, nor the circumstances of how they may have made the fateful decision to marry and to emigrate to the United States.

What is known is that there was no real future for them in the land of their birth. That era of Russian history involves growing dissatisfaction with the Tsar amid a quietly growing Bolshevik political upheaval movement, even within the borders of White Russia.

It is possible that Constantine faced potential conscription in the Tsar’s army. And family and friends had already begun making the journey to Pittsburgh where they hoped for a better life, sending letters back encouraging others to follow. In fact, nephews Ambrose Balysh and Martin Fursa (on the SS Rhein) came to America the same month as Constantine and Antonina.

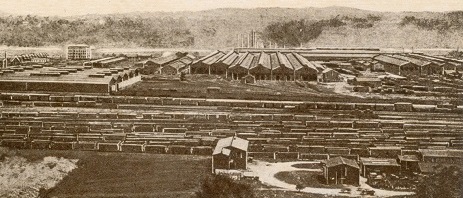

In 1904, Constantine embarked on the first of three ocean crossings to the United States, and made his way to Pittsburgh, sponsored by a "fourth cousin" by marriage, Vincent Sosnowfski, also spelled "Sosnowski." Constantine first worked in McKees Rocks, and saved his dollars. His employer likely was the Pressed Steel Car Company, known for recruiting thousands of unskilled immigrant workers from eastern and southern Europe. Rising labor unrest may have caused him to leave. In 1909, some 6,000 workers at Pressed Steel Car went on strike over "dangerous working conditions, low pay and industrial bondage that left them uncertain about their weekly wages," said the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.

|

| Pressed Steel Car Co., McKees Rocks near Pittsburgh |

While in McKees Rocks, circa 1905, he was a member of the wedding party for Vincent's marriage to Stefania Maskowski. Both men and/or their wives later served as godparents for each other's children.

Library of Congress

Constantine went back home to Smorgon about 1905. His perceived success made a great impression on his family and friends. They all thought he was rich.

About that time, says Moorehead's book, the Tsar "was in much more danger from his own people than from the foreign enemy." While there was plenty of food from good harvests, labor strikes and terrorist activities made it clearer that more political troubles were ahead and that there was no future for Constantine and his aspirations of self-determination.

Again in 1907, he returned to Pittsburgh as a single man, and got a job in the city's Highland Park section. But where? Again he worked hard and pocketed his earnings, thinking ahead toward his future.

Antonina's wedding gift icon

Constantine once more returned home to White Russia. On Nov. 23, 1908, in Antonina's village of Sutkovo, he and she were joined in matrimony. At her wedding she received an icon depicting the Virgin Mary and baby Jesus, a holy painting considered sacred in the Orthodox tradition.

They began to prepare for their own move to Pittsburgh, and within a month or two she became pregnant. To her he is said to have quipped, "In Amerika, they don't let people walk around barefoot like they do here."

One cannot imagine the heartbreak that the newlyweds faced with goodbyes to their parents and families. Despite the excitement of all that lay ahead, they knew deep down that they would never return or see their loved ones' faces again. Antonina seems to have spent the balance of her life with a continuing sadness that played out in an emotional distance with children and grandchildren.

|

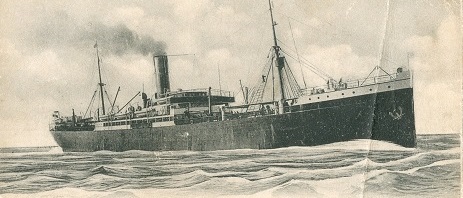

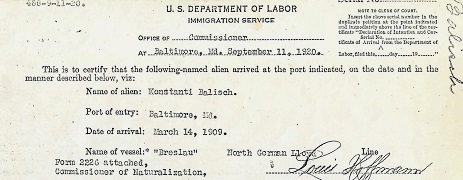

| Above: The North German Lloyd steamship Breslau, which brought the newlyweds to Amerika. Below: certificate of their arrival |

|

How Constantine and Antonina got there is not known, but on Feb. 27, 1909, they stood with their bags at the docks of the North German Lloyd shipping line in Bremen, Germany. Likely holding third-class tickets, for the cheapest sleeping room accommodations possible, the pair boarded the steamer Breslau. Thus began a 15-day trip across the Atlantic Ocean, bound for the Port of Baltimore.

As a veteran ocean traveler, Constantine may have enjoyed the trip, but the expecting Antonina was constantly seasick and nauseous, and clung to the cross on her necklace, a memory passed down several generations of her offspring. She also brought her new icon to the new land among the few possessions they could carry.

|

| Left: North German Lloyd Steamship logo and Constantine's passport |

Establishing a New Life and Home

The Balyshes arrived in Baltimore, MD on March 14, 1909 and cleared customs. From there they made their way to southwestern Pennsylvania, possibly as passengers on the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad which had a direct line to Pittsburgh.

Constantine, Antonina, Peter, ca. 1910

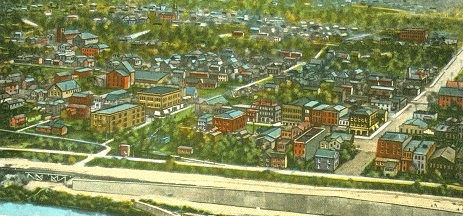

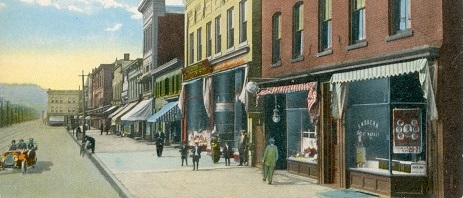

Upon arrival, they put down their first roots in Lyndora, in Butler County, 32 miles north of Pittsburgh. Lyndora was appealing as there already were pockets of Russian emigres living there, with a built-in social infrastructure and Russian Orthodox Church. As will be seen, the Orthodox congregations in Lyndora and later in Ambridge remained central to their lives.

Their firstborn son Peter entered the world on Oct. 18, 1909, some eight months into the couple's new life in the United States.

Constantine initially worked in Lyndora for the railroad manufacturing Pullman Car Company. He is said to have quit after he was scalded in a boiler explosion that killed a number of his co-workers. The couple then moved to another outlying Pittsburgh town, New Brighton, in Beaver County. There, he obtained work as a molder with Dawes & Myler, considered part of Standard Sanitary. In his labors, he helped make bathtubs and sinks.

Daughter Helen was born in 1911 and son John in 1913 in New Brighton. They joined the Holy Ghost Russian Orthodox Church in Ambridge. Their daughter Helen was baptized in the basement of the church building during the time it was being constructed.

|

| Views of New Brighton, PA, early 1900s |

|

They rented living quarters in a brick duplex at 628 Second Avenue, New Brighton, a block or so from the Beaver River. The other half of the duplex was occupied by the mother of their "fourth cousin" Mae (Schultz) Bayis. They took in boarders to generate additional income, but Antonina did not like the arrangement and never-ending work.

As she saw neighbor children play at the river's edge, with her own offspring growing, she also grew fearful that they might be susceptible to drowning. And when she became unnerved, the family said, she became "hyper" and at times "volatile." And when an opportunity came that provided a less dangerous means of support, Constantine and Antonina made another life-changing decision, to partially return to what they knew well, the stability of the soil.

|

| The Balysh farmhouse, circa 1973. Photos by Odger "Wayne" Miner. |

A Move to "The Farm"

The barn, November 1942

And so in August 1913, for the sum of $4,150 paid to Louis Albert Young, they moved to an old farmhouse nestled on a steep hill within a 100-acre, rectangle-shaped farm in New Sewickley Township, Beaver County. Located a mile west of the village of Unionville, the farm's address was considered New Brighton. Today the original outline is bordered in part by Pennsylvania Route 68 and Rothart Road and bisected by Druschel Road.

Their purchase was made official in a deed the following spring, 1914. The old house and farm not only provided shelter and a livelihood but was a focal point for family gatherings and a gathering place for relatives seeking a getaway, meals and a supply of free farm produce.

For another 17 or so years, Constantine kept his job at Standard Sanitary, driving there each day in his horse and buggy. He would work on the farm in evenings and on weekends. One day at Standard, he fell from a crane and injured his back, and was hospitalized for most of an entire winter. Antonina is known to have driven farm produce to New Brighton to sell every Thursday, "market day."

|

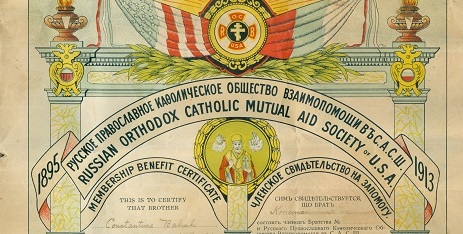

| Constantine's signed membership certificate in the Russian Orthodox Catholic Mutual Aid Society, 1913 |

Employers of that time did not have employee benefits plans and insurance protection for unskilled workers. So in January 1913, Constantine joined the Brotherhood No. 147 of the Russian Orthodox Catholic Mutual Aid Society, based in Wilkes-Barre, PA. In return for his dues of 86 cents per month, the Society promised to make payouts in case of long illness or death and burial, not to exceed $500.

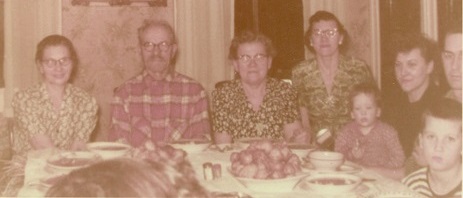

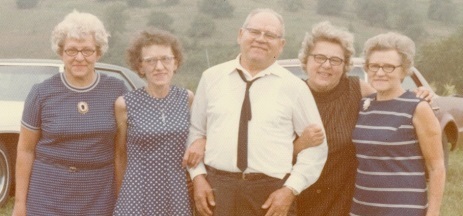

The balance of their children were born in the Balysh farmhouse -- Olga (1915), Sophie (1919) and Marie (1921). At intervals, formal family group photographs were taken, likely to send to loved ones in the Old Country.

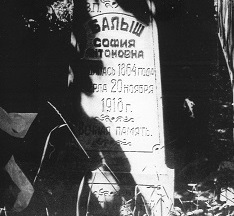

In these early years, Antonina received word that her father had passed away of pneumonia in 1914 and was buried in the Sutkovo village. Likewise, her mother died of pneumonia in 1918, having fled their village during the German invasion of World War I and hiding out with the children in a rough earthen dugout in the village of Krasnoe.

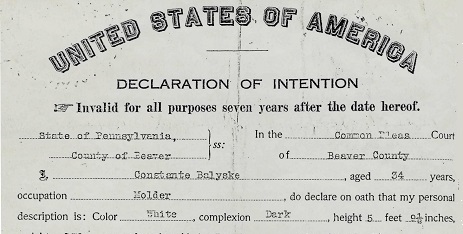

The year 1914 also was notable because in June, Constantine filed his declaration of intention to become an American citizen. In documents filed in the courthouse in Beaver, PA, he disclosed that he was age 34, held an occupation of molder, stood 5 feet, 9½ inches tall and weighed 170 lbs. He revealed that he had black hair, blue eyes, a dark complexion, and had been born in "Smorhoni," Russia. Unable to remember the name the ship which had carried them, he acknowledged arriving in Baltimore, swore that he was not an anarchist or polygamist, and renounced forever any allegiance to Tsar Nicholas II, "Emperor of All Russias."

|

| Constantine's declaration of intention to become a citizen.Courtesy Court of Common Pleas of the County of Beaver, PA |

One day while butchering, in November 1918, the Balyshes learned that the armistice had been signed, ending the First World War. Loud whistles blew throughout New Brighton. The close of the war would have been bittersweet, as it became known that the Russian Revolution was fully underway, that Tsar Nicholas II had abdicated the throne, and that he and his wife Alexandra and children had been executed in cold blood.

Courtesy Library of Congress

Constantine is known to have contracted influenza and was in bed from December 1918 to March 1919, at a time when a pandemic was sweeping the nation and killing millions. When he was strong enough to get up and dressed that spring, he walked to the barn and broke into tears after seeing how scrawny the animals had become.

Constantine and Antonina became naturalized Americans in 1921, after a mandatory eight-year wait. Over the years, he learned how to fluently read and write in English, while she did not. Why she chose to maintain what in effect was a language barrier is still a question.

The Balysh barn sat across the road from their farmhouse. The first barn was destroyed in a fire in 1920. Constantine did not discover the blaze until driving home one evening from the factory. Speculation was that broken glass lying about the barnyard had magnified the sunlight and ignited dry grass. Neighbor Frank Rader, a carpenter, helped him rebuild on the same site. The barn remained as a landmark of the property for decades, not only in housing animals and food stock, but as an unapproved play area for the grandchildren in the haylofts. The silo still stands as of 2023.

|

| Granddaughter and friend playing in the barn |

Constantine left Standard Sanitary in about 1930 after a Great Depression layoff. For the rest of his life, he was a full-time farmer.

To pay for the farm, Constantine secured a mortgage with Beaver Trust Company. Payments were due each February and August. Cash-poor in the early years of ownership, he could only pay the interest on the loan. It was not until daughters Sophie and Marie were old enough to go to work, and daughter Olga sent money from her job in Detroit, that he was able to amass enough to pay down the principal. In this way the daughters held a deeper emotional investment into their farm home.

|

| Family portraits as more children were born. Above with Pete and Helen. Below, back, L-R: Pete, Helen, John, Olga. Front children, L-R: Marie, Sophie. |

|

Sponsoring Nieces and Nephews as Immigrants

Independently, nephew Ambrose Balysh came to America the same month as Constantine and Antonina. His path led from New York and New Jersey to Minneapolis, Detroit and eventually to Pennsylvania. Over the years, estranged from his wife Anna (Pashkur), he and his children Nicholas, Olga Korby, Daniel, Walter and Michael "Mitchie" were frequent visitors to the Balysh home and table.

Within several years of their arrival in the USA, Constantine and Antonina became a magnet for attracting others of their family to emigrate. With Constantine as the youngest child in his family, there was enough of an age gap in some instances that the nieces and nephews were the same age as he.

|

| Above: L-R: nieces and nephew Martha (Balysh) Volinic, Frances (Fursa) Harlop, Anton Cybosky, Lena (Balysh) Wdovin. Below: nephew Anton on the Balysh porch. |

|

Nephew Sam Balysh came in 1910. Niece Martha (Volinic) arrived in September 1912, and Lena (Wdovin), daughter of Constantine's brother Leon, came in 1922 on the George Washington. Likewise, nephew Anton "Tony" Cybovsky, son of Constantine's sister Frances, and Frances Harlop, daughter of Constantines sister Helen, also emigrated in the early years.

Cousin Liza Balysh

Liza Balysh, a fourth cousin of Constantine's, came to the United States and married Anthony Bunkosky. The couple dwelled on a farm in Albion, PA. Niece Martha married Vladimir "Jim" Volinic and settled in New Brighton, PA, while her sister Lena wed Joseph Wdovin and lived in Butler, PA. Anton Cybovsky resided for a time in Albion, near Erie, PA, but was more of a vagabond without a permanent home, and ended up in California. Martin and Fannie Fursa dwelled in Bellevue until his death in 1940.

The Fursas would come to the Balysh farm and raid the garden without regard to paying for what they took. Constantine and Antonina allowed this to occur, but the actions angered their daughter Helen so much that she once told off Fannie Fursa for her lack of respect.

|

| Never-ending farmwork. Above, Constantine and Marie cultivating the fields. Below: Old Tony and young Wally Volinic raking hay. |

|

In 1925, word came by telegram that 38-year-old nephew Sam, a bachelor and Army veteran being treated at the U.S. Veterans Bureau Hospital in Michigan, had been struck by a train and killed. The body was discovered by the crew of a Michigan Central at noon that day, two miles west of Marengo and four miles east of Marshall. He was identified by a postcard in his pocket and a tailor's tag in his coat. Reported the Battle Creek Enquirer, "A scalp wound on one side of the head and abrasions on the face were the only apparent injuries. Coroner Weeks, who probably will not hold an inquest, believes the man was either struck by a train while walking along the tracks, or met with foul play and was thrown off a train. Life had been extinct for several hours."

Antonina's nephew Constantine Vashkevich

Nephew Anton Cybovsky would show up at times. He was not a hard worker, and one surviving photo shows him reading on the porch swing. After a visit in 1930, he wrote a note of thanks to his uncle, admitting guilt for having taken some vodka without permission.

It is surprising that none of Antonina's nephews or nieces ever came. After the close of World War II, her nephew Constantine Vashkevich, son of Vera, a decorated veteran of the Polish Army, but having fallen on hard times, wrote frequently asking for money and for help in emigrating. But he never was able to make the move.

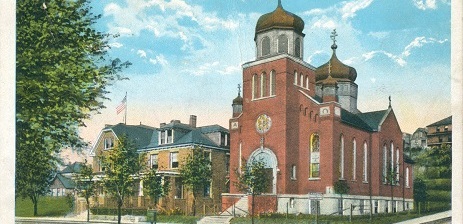

|

| Above: the Balysh church in Ambridge. Below, inside the sanctuary during daughter Sophie's wedding, 1968 |

|

Devotion to the Holy Ghost Russian Orthodox Church of Ambridge

The Russian Orthodox Church remained central to the Balysh family, in ways of the spirit but also as a place where Russian words and music could be regularly heard, a touch of the old homeland. In the early years, the family attended services in Butler, but after moving to New Brighton, they joined the Holy Ghost Russian Orthodox Church in Ambridge.

![]()

Mother's Day icon from church, 1945

The colorful interior of the small church was a source of pride. Religious paintings on the ceiling, walls and banners highlighted biblical scenes. The front of the sanctuary featured the iconostasis, a wall of sacred icon paintings of the saints, with a doorway to the nave. The smell of incense always seemed to linger in the air.

Easter was the major church holiday each year, and involved a late-night Easter Eve service after a period of fasting. The altar was highly decorated with flowers, as if heaped at a burial. The floral arrangements then removed at midnight as a symbol of Christ's resurrection, while churchgoers went outside to walk around the building three times, representing the days Christ had lain in the tomb. One of the Balyshes' daughters remembered that these services and blessing of the Easter baskets sometimes lasted until about 5 a.m. "Then everybody went home in a hurry and ate," she recalled. The services were so popular in the early years that the sanctuary was full to overflowing, with parishioners standing in the doorway and out into the yard, perhaps all the way to the street.

|

| Above, L-R: weddings of Olga (1939) and Marie (1945) at the Holy Ghost Church. Below: departing after the blessing service when the Balyshes celebrated their 50th wedding anniversary and the Jagerskis their 25th on the same day, 1958. |

|

Not as much is known about the church's Christmas traditions or other high holidays. When Constantine and Antonina marked their 25th wedding anniversary in 1933, they received a special blessing from their priest. Then again in 1958, at their concurrent golden anniversary and their daughter Helen's silver one, Rev. John Rachko gave another special blessing. The church had its own section for Orthodox burials at Sylvania Hills Memorial Park in the outskirts of nearby Rochester, with the Balyshes attending a dedication service there and buying eight plots.

Religious icons were displayed on the walls of the family residence, depicting the Virgin Mary, baby Jesus and the saints. These were considered holy, consecrated images in a form of artistry passed down from ancient times through the generations. In his book The Eastern Orthodox Church: Its Thought and Life, author Ernst Benz writes that the early church fathers "did not interpret icons as products of the creative imagination of a human artist. They did not consider them works of men at all. Rather, they regarded them as manifestations of the heavenly archetypes… a window through which the inhabitants of the celestial world looked down into ours."

Although not raised Russian Orthodox, this writer attended many services there over the years -- Antonina's funeral in 1966, Sophie's wedding in 1968, funerals of Frank Jagerski in 1973, Constantine in 1974 and Anthony Bulva in 1991, and many Easter Eve services with Helen in the 1980s and 1990s. The last were Helen's funeral in 2005 and Sophie's in 2012. A century-plus relationship between the Balyshes and the Holy Ghost Church ended with Sophie's passing.

|

| The Balysh children at the one-room Majors School, taught by Winifred (Hart) Zahn Ambrose (no. 1). They include Helen (2), John (3), Olga (4) and Sophie (5). Not pictured: Pete and Marie. |

A Growing Family

All of the Balysh children attended the local one-room Majors School in New Sewickley Township. Helen ended her formal schooling after the eighth grade. In the family value system, one's ability to perform chores and earn wages surpassed the need for knowledge. Olga appears to have been the first to complete high school and graduate in 1934. Helen once complained bitterly that all her mother ever wanted from her was work.

The never-ending farm toil was made easier or harder depending on the children's help. The Balyshes' eldest son Peter was never one for farming but preferred mechanical projects and repairing motor engines. He also seems to have been a bit of a ladies' man. One photo of him in his 20s shows that he had received a hair "perm" -- perhaps from his sister Olga -- and grown a mustache in preparation for a date with an attractive young woman.

|

| Pete at work on an engine, and with a mustache and perm |

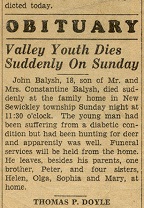

Peter relocated to Detroit and was there in 1930, employed as a mechanic, likely by one of the big automobile manufacturers. His absence from home rendered Constantine one less hand on the farm. The family underwent heartache when Peter eloped to West Virginia in December 1932 to wed his first wife, Mary Lloyd. The pair moved to Detroit's Highland Park neighborhood and bore a daughter, Bernice Ann. A brief period of joy turned to grief when the girl, suffering from a kidney tumor, died at age 13 months on Dec. 12, 1934. Peter and Mary produced another daughter Mary Jane, born in 1936. Peter sued for divorce in March 1939. Mary took her young daughter back home to live with her people, and there were no further relations between Constantine and Antonina and the granddaughter. In fact, when they sent Mary Jane a Christmas card one year, they received a reply envelope from the Lloyds, with their original card unopened and tucked inside. This artifact was kept by the Balyshes as a grim reminder of cruelty, and found by this writer among family papers circa 2004. The parents' worst nightmare took place in 1931. Their industrious son John, age 18, suffered from diabetes but otherwise maintained an active life and always was at his father's side on the farm. In December that year, he went on a three-day hunting trip with friends to Dubois, PA, and spent much of the time walking through cold, wet snow. Upon his return home he lapsed into shock and a coma and died in his bed. The road to the farm was so muddy and impassable that Constantine had to walk to a neighbor's home to telephone authorities, and learned they could not come to collect the body until the following day. He went from house to house to advise other neighbors, breaking down in tears each time. Adding to the indignity, Antonina was forced to cook for everyone who came to the house for the funeral service. For years afterward, Constantine said that "I would rather have lost my right arm." With one son of limited help, and another in the grave, Constantine hired a number of laborers over the years. These typically were bachelors or men whose wives were still in the old country, without any plans for reunification. Among them were Frank Baran, Victor Lyhoke, Victor Shoroh ("Old Victor") and Antonio Barbiere ("Old Tony"). They lived at the farm and were considered part of the extended family. Old Victor had a particularly difficult personality and was feared. How this behavior was allowed is not known, other than he must have been an exceptional worker. Christmas Eve suppers were always a highlight especially as the years progressed and the children married and scattered. Antonina's menu featured the traditional meatless Russian dishes of smelts soup, fish, pickled herring, sauerkraut as well as raisin-filled doughballs, all served on a tablecloth with small mountains of straw underneath. A bottle of vodka helped wash it all down. Several of the laborers were Italian. They are the reason why spaghetti was served at Christmas Eve suppers in addition to the traditional fare. For decades after the last of these men died, spaghetti remained on the Christmas dinner table for the grandchildren and great-grandchildren who wanted no part of the smelts soup or herring. The First World War Devastation in White Russia The Balyshes spent the First World War years relatively unscathed. Only their nephew Sam, living at the time in Toledo, OH is known to have served in the U.S. Army, as a member of the 159th Depot Brigade. But back in Old Russia, in the path of the invading Germany army, the villages of Smorgon and Sutkovo were maimed. Whatever quality of life had been known up to that time was destroyed amid the killing, shelling, trenches, starvation and hopelessness. Antonina's brother Casimir, who had studied at a theological seminary, fled to Russia and joined the Red Army. Symbolizing the collapse of civilized life and hope wrought by World War I, the ship that brought Constantine and Antonina to America, the Breslau, was sunk in the Dardanelles by British mines in January 1918. Without international mail service during the war, the family was emotionally and temporarily sheltered from the extent of the horrors. When their niece Lena came to America in 1922, she likely brought stories of the wartime hardships. But in 1928, a starker truth came to light in an extraordinary letter and photograph the Balyshes received from the newly appointed priest of the Sutkovo church in the old country. Rev. Platon Sliz was boarding in the household of Antonina's brother Grigorii, and when learning of family in America, took the address and sent an impassioned letter and photo. ...remained without a roof over their heads, without a slice of bread and till now leading a pitiful way of life wandering about what remains of the war trenches and living in damp war dug-outs. Many people do not even have this because the war took away their parents or last son bread-winner. These unfortunate wretches fall of exhaustion in the night, freeze to death, looking for a pitiful refuge and being hungry without a dry crust of black bread and a drop of water... Continuous trenches cut up every strip of earth, endless serpentine lines of barbed wires, countless number of shell-holes and dug-outs, this all is [on] property of our Sutkovo parishioner. Our parishioner is poor but our church is even more poor. It stands on the first line of Russian trenches and the merciless, insidious German did not spare its holy walls. In conclusion, I ask you, Highly Reverence, to read [this] letter to your true parishioners at Sunday's service and beg them to respond to our call in order that it may not become a "voice crying in the wilderness." We are poor, we want to pray and we ask you do not abandon us, to give your hand to "drowning men." One can only imagine the anguish that such a letter caused the Balyshes and anyone else with whom they may have shared it, certainly their priest and fellow worshippers of the Ambridge congregation. Perhaps some sent money and offered up prayers. As noted earlier, Antonina reacted by weeping for a week. The Great Depression and the Horrors of World War II Unknown to the Balyshes until much later, their niece Stella Balysh, daughter of Constantine's brother Larry, died sometime during the 872-day military blockade of Leningrad (St. Petersburg) during the Second World War.

Antonina lost touch with her brother Aleksandr, and feared he had been killed in one of the wars. Years went by without any word of his fate. What she never knew is that in 1923, he had been discharged from Red Army, and then in May 1938 was arrested and shot five months later in October 1938, believed to have been executed by the hand of the Soviet secret police. The family was in the news in June 1931 when son John, driving his mother and sister Helen on a hill between Marion Hill and New Brighton, collided with a vehicle operated by Thomas Agnew of Beaver Falls. They "sustained minor cuts and bruises," reported the Beaver Valley Daily Times. "Balysh and another man riding in his car and Agnew's wife and small child were uninjured in the crash. Mrs. Balysh and her daughter were treated by a physician and went home. Private Edward Foust, of the state highway patrol, investigated the accident." A potentially deadly feud between Constantine's hired hands generated unwanted news in February1938. Said the Daily Times, "a peaceful cow was the only casualty when a New Sewickley township farm hand went gunning for a fellow-employe with a single-barrel shotgun." Tony Barbare, 68, the farmhand, was in Beaver County jail today, charged with pointing a deadly weapon, at John Trosky, who also lives on the Balysh farm... Constable William Mohrbacher of New Sewickley took Barbare into custody Thursday evening, after, it is alleged, Barbare had fired three times at Trosky. Mohrbacher said Barbare, who had lived at the Balysh farm for 16 years, evidently had been drinking cider and had an argument with Trosky. Going into the house, he obtained a gun owned by Balysh and fired it at Trosky, who took to his heels and ran across the field. Witnesses said Barbare followed, re-loading the gun as he ran. A cow fortunately for Trosky but unfortunately for the cow, got in the way and was liberally stung with pellets from the shot gun as Barbare fired again. The chase continued, with Barbare firing a third shot before the fleeing Trosky outdistanced his aged but determined pursuer. During World War II, two distant cousins from nearby Brighton Township lost their lives at war -- John Sosnowski in Europe and his brother Vincent in the April 1945 torpedo-sinking of the Pringle in the South Pacific. A year after the war ended, tragedy was compounded when another brother Paul Sosnowski was killed in a hunting accident in Elk County, PA. Today John's and Vincent's names adorn a war memorial in Beaver's central park, with Vincent's name also inscribed on the tablets of the missing in the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific in Honolulu. The two brothers also were pictured on the front page of the Beaver County Times over the Memorial Day Weekend in 2009. The Balyshes' grand-nephew, Nicholas Volinic, son of Martha and Jim, learned how to fly. He amused the family more than once when landing his small airplane in their farm field. He even is known to have taken one of the Balyshes' young granddaughters up for a flight one day. But tragically, Nicholas and two others were killed in a crash in 1946 near Effingham, IL, with the aircraft clipping a tree during a forced landing. Weddings of family and friends always brought pleasure. Part of the tradition was for a group photograph to be made of the bride, groom, attendants and wedding party. Images found in the Balysh papers show groupings in the marriages of Pete Zibaila, with Peter and Helen among a group of 17; Nick Klutka; niece Ephronia "Frances" Fursa to Jacob Harlop (1911); niece Lena Balysh to Joseph Wdovin (1923), with Constantine, Antonina and Helen pictured; and niece Martha Balysh to Vladimir "Jim" Volinic (1915). Other formal photograph portraits that were kept show niece Frances Harlop Dobino and her daughter and son in law Sophie and Louis Hays; Peter and Kathryn Schultz and their daughter Mae (Schultz) Bayis; George Shirocky; Alex Kozlowski Jr.; and Nicholas and Dorothy Yurkovich. With two of their married children Peter and Olga now living and working and raising families in Detroit, and many other of their extended family in the Motor City, the 1930s, '40s and '50s involved frequent trips back and forth. As grandchildren were born and grew, there were always birthday parties and cakes at the farm. Sophie remained at home during those years and often drove her parents on day trips to visit family and friends in Pennsylvania and Ohio. There are still Balysh cousins in Michigan as of this writing in 2023. Stories of the Balysh Offspring At the age of 34, Peter married a second time, in Detroit in 1942, to 38-year-old Julia (Ceila) Chapor. They went on to bear one daughter of their own, Patricia Balysh, an opera singer also known by her stage name of "Erica Arnold." Eventually they moved to Livonia, MI. Daughter Helen and her husband Frank Jagerski settled in Monaca, PA. They became the parents of two children, Constance Miner and Frank Joseph Jagerski Jr. Daughter Olga was wed on June 22, 1939 to Edgar Avey, in nuptials at the family church in Ambridge. A related news story said that "Guests were present from Detroit, Youngstown, Ellwood City, Pittsburgh, Butler and valley towns." They settled in Detroit and produced a family of two -- Alexandra "Sandy" Blount and Gary Avey. Daughter Sophie did not marry until later in life, devoting herself to her work as a nurse and as a caregiver to her parents. On her father's 88th birthday, May 19, 1968, she wed Anthony J. Bulva. They made their residence in Sophie's one-story home on her section of the old farm. Daughter Marie was united in marriage with Victor Woodrow Simpson Sr., in the family church on May 11, 1945. Their five offspring are Victor Woodrow "Woody" Simpson, Antoinette "Toni" Wells, Gregory Simpson, Lucretia "Lu" Black and Bruce Simpson. They spent their years in Industry, PA. Final Years The Balyshes lived the rest of their long lives on the farm. More grandchildren and now great-grandchildren were born, to the Balyshes and their nephews and nieces, adding to the headcount of the family. Christmas Eve suppers were held year in, year out. "Russian Easter" meals were served for anyone who could come. Antonina must have had a lift in spirit when letters began to arrive more regularly from her sister Vera Vaskevich and cousin Kapitolina "Lena" (Balysh) Guseva from what was now the Soviet Union. In November 1958, Constantine and Antonina celebrated their golden wedding anniversary, attending a church service and hosting a reception at the farmhouse. As he aged, Constantine complained that his days were numbered. "I don't think I'll make it through the year," he groaned to his son-in-law Frank when turning age 70. In truth he survived another 24 years after that, and in a twist of fate outlived the son-in-law. He also survived being gored by a bull and falling from an apple tree, breaking bones. Antonina's health was more fragile and in the 1960s she suffered a number of mini strokes. At the end she was admitted to the Beaver Valley Geriatric Center, where at the age of 77 she died on Feb. 2, 1966. An obituary in the Beaver County Times said she was survived by 11 grandchildren and one great-grandchild (this writer). Constantine lived for another eight years as a widower. His daughter Sophie was married on his 88th birthday in 1968. He marked his 90th birthday in May1970, with a family gathering and cake at the farmhouse. Around that time daughter Sophie built her own house on a section of the farm, and he spent his final years in a hospital bed in her living room. He passed away at the age of 94 on Aug. 8, 1974, the same evening made famous in American political history with the resignation of President Richard Nixon following the Watergate scandal. Word came in 1981 that Antonina's last living brother, Casimir, had died in White Russia, known as "Byelorussia." Photos were sent showing the funeral procession. Some 14 years later, in August 1989, Sophie and Helen hosted a visit from Casimir's daughter Lena and granddaughter Olga Guseva, who traveled from their home in Riga, Latvia. They stayed for a month, and it was the first time the families had connected in person in eight decades. Sophie hosted the last of her Christmas Eve suppers in 1994. Other Select Images

Granddaughter Bernice Balysh

John with cousin Mitchie Balysh; obituary and grave marker

One of the happy highlights of their lives during the Great Depression years was their 25th wedding anniversary in 1933, followed two days later by the marriage of their daughter Helen to Frank Joseph Jagerski Sr. While the Jagerski nuptials were held in the family church in Ambridge, by the hand of Rev. Peter Karel, the reception party was held at the Balysh farm. The eating, drinking and merriment lasted for three days. Frank's kid brother Carl later recalled there was so much dancing that he thought the couples would twist right through the floor and down into the cellar. In one snapshot taken at the farm party, Antonina actually seems to be wearing a smile.

(left) and Olga on Helen's wedding-day, 1933

Never-ending farmwork. Above: cutting oats. Below: Sophie at the reins.

Christmas Eve 1954, with niece Martha Volinic (left) and the Simpsons, right

Constantine's birthplace, Smorgon, bombed and slashed by trenches of the Germany army during World War I.

Rev. Platon Sliz and his bombed-out church in Sutkovo

The photograph shows Sliz among other men standing in front of the church, which had been bombed in the German invasion, its roof destroyed and stone walls opened with huge gashes. Sliz's beautifully penned, four-page letter on legal-size paper begged for help, agonizing that his Sutkovo congregation had:

How does one sum up the complex tapestry of a family of parents and children growing to maturity during a boom and bust periods of American history, the Roaring 20s followed by the Great Depression of the 1930s followed by World War II? One cannot even begin to imagine the horrors inflicted on the Balyshes' loved ones during this era in Byelorussia, with some of the land now part of Poland thanks to political subdivision.

Niece Stella

For this purpose, here are some highlights of those years.

Antonina's brother Ivan was captured during the Second World War and died in captivity on July 20, 1944. Her nephew Igor, son of Casimir, who trained as a tank officer in the Soviet Army, was killed during the Siege of Leningrad on Oct. 11, 1942. Antonina's brother Grigorii was a partisan during and after the war, trying to help liberate Byelorussia from Polish control. When the conspiracy was discovered, he defected to Russia and was imprisoned until his release in 1946.

In the United States, after his divorce, Peter went to live in Glassport on the outskirts of McKeesport near Pittsburgh. At the age of 30, circa 1940, he was required to register for the military draft, and disclosed that he was employed at the Irvin Works of United States Steel Corporation. While there, he is believed to have met his future second wife, Julia.

Daughter Olga relocated to Detroit during the 1930s and became licensed as a beautician. She resided with her cousin-by-marriage, Anna (Pashkur) Balysh and her family as shown in the 1940 census enumeration, earning a living in a beauty parlor.

It was such an event in 1942 when electricity was installed at the property that Sophie took photographs of the lineman at the top of the pole. The farmhouse did not have indoor plumbing until the late 1940s when installed at the top of the second floor steps by Louis Hays, a Harlop grand-nephew by marriage. To be sure, the outhouse in the backyard remained in use, as well-recalled by this writer from his childhood.

Getting electricity, 1942

Above: L-R: brothers Vincent and John Sosnowski, killed in WWII, photos courtesy Neal Frederick -- and the war memorial in Beaver, PA bearing their names. Below: grand-nephew Nick Volinic, who liked to land his airplane in the Balysh farm fields, killed in a 1946 airplane crash in Illinois.

Above: wedding of niece Ephronia "Frances" Fursa to Jacob Harlop, with Antonina (back, center) in the wedding party. Below: 1914 marriage of niece Martha Balysh to Vladimir "Jim" Volinic, with cousin Liza Balysh standing, center.

Above: marriage of friend Pete Zibaila and Anna Mary Bustavich, with Helen seated at far right, Peter Balysh stands 3rd from right and cousin Sophia (Harlop) Hays 2nd from right. Below: 1923 wedding of niece Lena Balysh to Joseph Wdovin, with Constantine and Antonina in the back row, center, and Helen seated at left.

A highlight of every week was Thursday, "huckstering day." Constantine would load his truck with fresh farm produce and drive to New Brighton, going door-to-door to sell. He often took along his grandchildren and their friends who helped with the work. Afterward, he would stop for lunch and a beer and treat the kids to a salami sandwich and cold drink. He also visited Keystone Bakery in Bridgewater to buy day-old bread to feed to his livestock.

50th wedding anniversary, November 1958. Below, standing L-R: Vic and Marie Simpson, Helen and Frank Jagerski, Antonina and Constantine, and Peter and Julia. Seated, L-R: Olga and Edgar Avey, Rev. Fr John Rachko and Sophie.

Above: Constantine's 90th birthday party, May 1970. Below: gathered for Constantine's funeral, August 1974, L-R: Marie, Sophie, Pete, Olga, Helen.

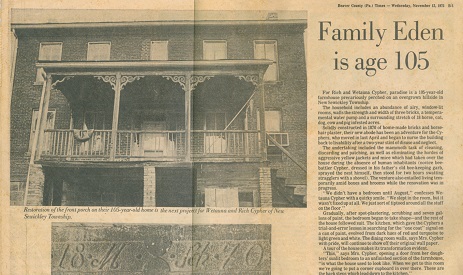

Sophie sold the old farmhouse to Richard and Wetauna Cypher, who then undertook a renovation. The house received a full-page of photos and a story in the Times dated Nov. 12, 1975 and headlined "Family Eden is age 105."

Constantine and Antonina cultivate their garden

Above: Helen's 1933 wedding to Frank Joseph Jagerski Sr. She chose as her bridesmaids, L-R: Mae (Schultz) Bayis, Sophie (Harlop) Hays and sister Olga. Below: Olga's 1939 wedding to Edgar Avey, with her sisters Sophie (center) and Marie as bridesmaids and niece Connie as flower girl.

Above: Wedding of Marie and Victor Simpson. Below: feasting on blessed food -- ham, kolbassi, eggs, bread, cheese -- after an Easter midnight mass, 1953.

Above: a visit with nephew Anton Cybosky at his home, Albion, PA, 1951. Below: Antonina and daughters Olga and Sophie at Gary Avey's baptism in Detroit, 1940s

The last of the barn, 1973-1974

Above: Beaver County Times article, 1975. Below: Balysh Reunion at Armco Park, August 1977.

Funeral of Antonina's brother Casimir in Byelorussia, 1981.

Copyright © 2023 Mark A. Miner