Eva Maria (Weber) Meinert’s Arduous Girlhood Immigration Journey, 1708-1709 |

|

Weary of wartime destruction, high rents and taxes, and a cruelly cold winter, thousands of poor Germans left their homes from May to November 1708 to embark for new lives and freedoms in the American colonies. Among them were the families of Johan Jacob and Anna Elisabethe Weber, Johannes "Jacob" and Anna Christina (Mauer) Boßhaar Sr. and Balthazar and Elisabetha Wennerich, who all are profiled on this website.

The Webers' daughter, Eva Maria (1704?-1776), who later wed Friedrich Meinert (1695?-1751), was age four or five when she and her parents embarked on their journey to America. Although she lived a long life, she may have harbored few memories from that young an age.

|

| William Penn |

~ The Disaster of Germany, 1708 ~

Germany of 1708 was nothing at all like today. It was not a unified nation or have a central, regulated money system. Rather it was a patchwork of more than 50 free cities and several thousand governing authorities, many in conflict with each other over power and authority. There were different dialects and customs. The ruling classes mainly were self-serving with constant conflicts over the others' Protestant and Catholic church affiliations.

The greatest German geniuses had not yet been born, among them Goethe (1749), Beethoven (1770), Kant (1774) and Schiller (1759). Bach was in his early 20s, working as an in-house musician at Protestant churches. There was not yet a national identity.

Germany's peasant and working classes of the era have been described by author C.V. Wedgwood as "powerless, ignorant and indifferent."

There was much from which to despair. The Peasants War of 1525 followed by the Thirty Years War which ended in 1648 had brought waves of invading armies from Spain and Sweden and left a wide swath of the destroyed landscape. Towns, churches and farm fields were destroyed. Lands variously were confiscated by whatever army or prince held them at the time. Thousands were dead over several generations of families. Many other thousands had dispersed. Writing in The Germans in Colonial Times, Lucy F. Bittinger called the Thirty Years War “unimaginable and indescribable” –

It is difficult to call up to one’s mine what this event was. Many portions of Germany became uninhabited wilderness; many of the miserable people became in the extremity of their distress robbers, murders, and even cannibals. The free peasants were degraded to serfs, the rich and energetic burghers became narrow-minded shopkeepers, the noblemen service courtiers, the princes shameless oppressors.

These wastelands remained for many years thereafter.

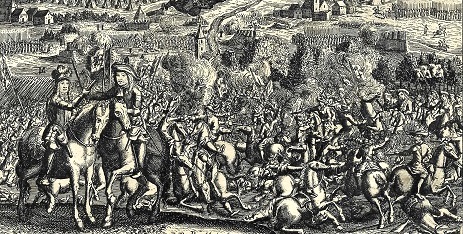

|

| Battle of Sinsheim, Germany, in the years leading up to the Weber emigration |

|

| French commander Marechal Villars, whose armies destroyed the Rhine region |

Then in May 1707, during what's known as the “Spanish Succession,” war came again. French armies once more invaded with fury, led by King Louis XIV’s military commander Gen. Claude Louis Hector de Villars (Marechal Villars). The towns of Wurtemberg and Stuttgart especially were devastated and plundered in these hostilities. Villars is said to have forced the locals to pay more than 9 million gulden in tributes or fines, considered an incredible sum at the time.

In addition to wartime damages, the German commoners had to pay increasingly higher taxes, assessed by the ruling princes of these regions – to cover their lavish lifestyles and the costs of war. Unlike today, tax revenues were not used in rebuilding the communities and infrastructure, but rather to line personal pockets. There was just no money in the system.

Adding to the misery, a heavy frost in January 1709 and heavy snowfalls into the next month in the Rhineland caused widespread misery. Hundreds of people died, animals and birds froze to death, fruit trees and vineyards upon which livelihoods depended were destroyed, and once more the human spirit crushed.

At about this time, the English Queen Anne and Parliament were mulling over plans to populate the American colonies with Protestant immigrants. Their objective was both financial and military.

The Crown’s Royal Navy had a desperate need for hard-to-get and otherwise unaffordable supplies for its shipbuilding, especially tar products. It was believed that the large body of German immigrant laborers could be put to use to harvest large forests of American pine, extract the tar and ship it to England at a lower cost than would be affordable on the open market in Europe.

~ Enter Rev. Kocherthal and the Appeal of America ~

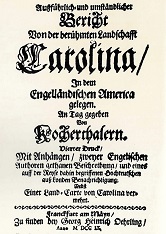

They were attracted to the idea of life in America as a result of extensive advertising over many years by the English government as well as entrepreneurs such as William Penn and Rev. Josua Kocherthal. Penn, an Englishman, had made perhaps three trips to Germany trying to generate public interest in a mass relocation to help populate his new commonwealth, Pennsylvania.

|

| Kocherthal's broadside advertising America |

The Webers and their daughters Eva Maria and Elisabethe were among the first of these parties to go. They boarded boats on the Rhine River in May 1708 and headed toward the port city of Rotterdam, Holland.

These slow-moving voyages took some four to six weeks. Along the way, as they stopped for provisions or to pay tolls, the groups occasionally received funds and supplies from sympathetic communities.

From Rotterdam, the emigres boarded ships to take them to London, a relatively short passage of six to eight days. As word spread, even more discontented Germans joined the movement. At one point, 1,000 per week were transporting from Rotterdam to England, including many youngsters. By October 1709, some 13,100-plus had arrived in London, with English authorities becoming alarmed and halting arrivals. Some professed Catholics, unwelcome, turned back.

London in turn became crowded with the unexpected volume of refugees who, although expecting an immediate transfer to American-bound ships, were forced to stay put. As written by Walter Allen Knittle in his book Early Eighteenth Century Palatine Emigration, “No one stood ready to carry out such a program… [This] avalanche of people was like a flood instead of rain.”

For many months, they camped at Blackheath, Greenwich and Cumberwell, and at taverns, town squares, warehouses and other sites. They daily attracted crowds of curious Londoners. The Germans generally were well-behaved. But threats against them were made, fights broke out, begging for bread was rampant and sanitation was poor. William Penn, in debtor’s prison, was of no help. The Crown and churches helped generate limited donations. But the arrangement was not a sustainable.

|

| The Webers among thousands of Palatine emigrants camped for months in London, while awaiting passage en route to New York |

Kocherthal’s party included the Weber family. Upon their arrival in London, Kocherthal made a petition to Queen Anne for help. She in turn gave orders that the emigrants be given clothing, coal and tools. Parliament, churches and a public subscription campaign raised additional monies.

While plans were considered to send the Germans to the Carolinas or Virginia, the site eventually chosen was the Upper Hudson River region 55 miles from Manhattan.

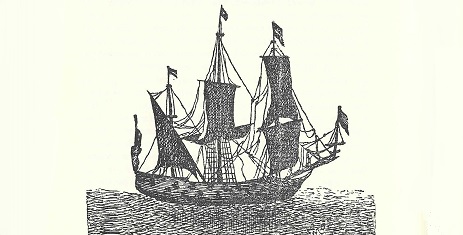

~ Aboard The Globe, Sailing from London ~

Finally in October 1708, the Kocherthal party sailed for New York aboard the ship, the Globe. The trip took nine agonizing weeks. Conditions were crowded. An estimated 20 percent died en route, including many children. A few babies were born and baptized in port or on the high seas. In fact, one of the infants was the Webers’ third child, Johann Herman, whom Kocherthal baptized on Sept. 14, 1708, recorded in his journal as “on board the Ship Globe.”

The Globe finally arrived in the New World in December 1708. But cold weather and the frozen port forced the travelers to stay aboard. They endured further misery when going without ample drinking water or foodstuffs.

When the inclement weather finally broke, the migrants were ferried up the Hudson River to the mouth of Quassaick Creek, near today’s Newburgh. They were free to debark and inspect the landscape of their new home. Lots were drawn for individual tracts of land. The emigres were issued food, supplies and even rum as well as tents, guns and ammunition and cauldrons.

|

| Tranquil Hudson River near Newburgh, the Palatines' new home in New York |

“Subsistence lists” were made naming each family receiving these items, including the numbering of adults and children, with the Weber, Boshaar and Wennerich among those recorded.

Other clusters of German migrants in London were forced to wait until late December 1708 to sail for the colonies. These ships arrived in June 1709 at New York’s Nutten Island, also known as Governor’s Island, and then proceeded up the Hudson.

Among those who made the voyages were New York Gov. Lovelace (in 1709), the teenager Conrad Weiser of Herrenberg, Württemberg, who became a famed interpreter and diplomat between Pennsylvania and Native American peoples, and the orphan boy John Peter Zenger of Rumbach, Germany, who would become known for his defense of freedom of the American press.

|

| New York Gov. Lovelace (left) and Commissioner Livingston |

|

| Fellow emigre Conrad Weiser Courtesy Wikipedia |

Over the next two years, the tar production plan had sporadic results, as the Hudson Valley was hilly and not dense with pine. Many German laborers felt they were being treated like serfs and disliked the conditions of their labor. Knittle wrote that:

For the most part husbandmen and vine-dressers, they were dissatisfied with their work and their location. They disliked to work in gangs and under rigid supervision. There was no incentive to work hard to pay back the funds spent on them; they sought only to receive the forty acres each of soil for their settlement.

~ End of the Experiment ~

But in 1712, New York Gov. Robert Hunter, who had funded much of the investment out of his own pocket, decided to end the experiment. The Palatines were told in September 1712 that they would need to subsist on their own. If choosing to move elsewhere, they would need to register and secure a ticket. Somehow they had to find a way to survive the upcoming winter and hold off starvation.

Many relocated to the town of Schorarie, NY, despite Hunter’s objections. Here the soil was fertile, and the local Native Americans friendly. The people were taught how to find edible herbs and roots in the woods and given fur robes for warmth. Wrote Knittle:

The Palatines had large families as a rule, the children often numbering close to twenty or more, but the mortality was exceptionally high. The maidens married quite young, increasing their fecundity. The Palatine women were generally robust and strong, for within one week of their arrival in Schoharie Valley four children were safely born.

From this, without benefit of good tools, sprung creation of seven villages in the Schoharie area. Without horses and wagons, the people hand-carried their supplies, including salt and wheat seed needed from afar. Wrote Bittinger, “For a generation, until the first mill in Schoharie was built, the pioneers, men and women, carried their grain upon their backs to Schenectady to have it ground into meal, large companies of them going together and camping overnight in the woods on the way.”

In his personal journal, Weiser wrote that “Here the people lived for a few years without preacher, without government, generally in peace. Each one did what he thought was right.” Where the Webers, Boshaars and Wennerichs dwelled during this time is not known.

~ The Palatines' Migration to Pennsylvania ~

Then in the late 1710s, perhaps encouraged by new Pennsylvania Gov. Sir William Keith, some of these families began a migration south into Pennsylvania. Bittinger wrote that:

Under the guidance of their faithful Indian friends, they cut a road through the forests from Schoharie to the head-waters of the Susquehanna; here they built rafts and canoes, placed on them the women and children and their furniture, and floated down the river, the men driving the cattle along the land. Arrived at a point where the Swatara empties into the Susquehanna, they ascended this stream until the expedition reached the mouth of the Tulpehocken. Here the Germans selected their land and settled, finally, after fourteen years of wondering from place to place – from the Palatinate to London, from London over-seas to the camps on the Hudson, thence escaping to Schoharie, they were finally at rest in Pennsylvania. The story of this exodus of these poor Palatines, cast down but not destroyed, baffled, oppressed, plundered, but never discouraged, is a tale with few parallels, and one of its marvellous incidents is this journey through the forests; yet the people themselves seem not to have thought it anything worthy of note.

Berks County, PA was considered a very safe and welcoming destination for the Palatines. There, the Webers settled, in the Oley Valley. In the 1820s, their daughter Eva Maria entered into marriage with Friedrich Meinert, also of Oley, and began the vast Minerd-Minard-Miner-Minor family of which many tens of thousands have been born over 300 years' time.

The Boßhaars' son Johann Joerg married the Wennerichs' daughter Mary Elizabeth. They too migrated from New York and settled in Lancaster County, PA. They put down roots in what became the small farming village of New Holland, about 13 miles east of the county seat of Lancaster.

Many years later, historical artifacts and relics from the pioneering era were preserved and years later place in the Old Stone Fort Museum near Schoharie.

|

| The 1735 libel trial of the Webers' fellow emigre and Philadelphia publisher John Peter Zenger. Here, his attorney Andrew Hamilton claims, "It is not the bare printing and publishing of a paper that will make it a libel - the words themselves must be libeous, that is, false, scandalous and seditious, else my client is not guilty." |

~ For Further Reading ~

The Germans in Colonial Times, by Lucy F. Bittinger. Philadelphia and London, J.B. Lippincott Company, 1901.

The German Revolutions, by Friedrich Engels. Chicago and London, The University of Chicago Press, 1970.

The Thirty Years War, by C.V. Wedgwood. NYRB Classics, 2005.

Early Eighteenth Century Palatine Emigration, by Walter Allen Knittle, Ph.D. Philadelphia, Dorrance & Company, 1937.

The German Immigration Into Pennsylvania, by Frank Ried Diffenderffer. Baltimore, Genealogical Publishing Co., Inc., 1988.

The German Genius: Europe's Third Renaissance, the Second Scientific Revolution, and the Twentieth Century, by Peter Watson. Harper Perennial, 2011.

Copyright © 2022 Mark A. Miner