|

Seven

Things Mama |

| Afternoon Remarks at the July 2015 National Junghen- Younkin Reunion, Kingwood, Pennsylvania |

|

By Mark A. Miner |

|

|

|

2015 reunion group photo |

~ The Soldier with Two Widows ~

It seemed to be a typical Civil War tragedy. Jacob Younkin, a farmer boy from the mountains, got married, went off to fight for his country and was killed in action. The government awarded a pension to his grieving widow to compensate her for the loss. In short, it was a cut-and-dried case, with all the facts in order, however sad.

Except for one key complication. Two women stepped forward after his death, each claiming to have been his wife, each with proof of marriage performed by a minister of the gospel. This is the stor the matrimonial mess, involving "Widow Sarah" and "Widow Mary Jane", one of them legitimate, the other bogus. But who?

The soldier was born on a farm near Kingwood in about 1840, the son of John M. Younkin and Laura Minerd. In about 1860, he moved to nearby Normalville, and a year later, when the Civil War had been underway only a few months, he left home to enlist in the 85th Pennsylvania Infantry. The 85th trained in Uniontown at Camp Fayette before marching toward the battle lines in Virginia.

|

|

|

Burial of soldiers and burning of dead horses after the Battle of Fair Oaks Station, near Richmond, where Jacob Younkin was killed in the Civil War |

In May 1862, in the Battle of Fair Oaks/Seven Pines, the 85th took a position in rifle pits on the right side of the main work. During seven days of extended fighting, Union and Confederate losses totaled 11,000 men. The 85th Pennsylvania itself had 87 casualties, including our Jacob.

The news quickly reached home. Jacob’s name was printed in a casualty list in the Uniontown Genius of Liberty.

Four months later, 26-year-old Sarah Floyd (Miller) Younkin (or "Widow Sarah") appeared in Fayette County court. She claimed she was the widow and was thus entitled to a widow's pension. She showed documents proving the marriage which took place shortly before the regiment left town.

The paperwork was in order, and the government approved Widow Sarah's pension, at a rate of $8 a month, retroactive to May 31, 1862, the date the soldier died. She thus received a windfall of a year's worth of payments.

The monthly checks suddenly stopped five months later. Something was amiss. It turned out that officials had discovered something that Widow Sarah may never have been told – that her husband was also married to a woman named Mary Jane ("Widow Mary Jane") and had a young son named J. Harvey Younkin living in the mountain.

Confusion ensued. Investigations were launched. The dust did not settle for years.

Documents and witnesses were furnished to show that the soldier had married a cousin, Mary Jane Christner, the daughter of Levi Christner and Catherine Younkin. Though she had remarried since the soldier’s death, her young son Harvey was entitled to it.

What officials learned that while in basic training in Uniontown, just four days before marching to the front, Jacob got drunk and married a prostitute. One observer said that “I am satisfied that Younkin was drunk when he married this Sarah Floyd, who was well known as a prostitute, and that he did not care, as he would not then be detected as the Regt was then under marching orders.”

With all the new facts in hand, the government recognized Widow Mary Jane as the soldier's true wife, and it granted young Harvey Younkin's pension in August 1869, more than seven years after his father's death.

How Widow Sarah reacted, or whether she ever refunded the money erroneously paid to her, remains a mystery.

|

|

|

Younkin Cemetery, Paddytown |

~ Mysterious Disappearance~

Sarah Jane Younkin – daughter of Rev. Herman Younkin and Susannah Faidley, was born in 1859 in Upper Turkeyfoot. She wed John Franklin Colflesh. Their surname was the Americanized version of Kalbfleisch, German for "calf flesh" or, more simply, "veal."

In the early summer of 1884, pregnant with her first child, Sarah Jane mysteriously disappeared. This caused "quite an excitement at Paddytown," said the Somerset Herald. The article said that:

|

|

|

Somerset Herald, 1884 |

Mrs. Kalbfleisch has been laboring under mental depression for some time, from sickness. On last Friday she wandered away from home, no one knowing what direction she had taken. Search was immediately made by the family, but the missing one could not be found. The search was resumed on Saturday, with no better result. The news spread rapidly, and on Saturday about one hundred people were assembled and divided into squads of about ten persons each, and the entire neighborhood for miles in all directions was scoured, but yet no trace of the lost one could be discovered. About 6 o'clock in the evening the crowd returned from their labors, and an understanding was had that all should return early on Monday morning to resume the search.

The neighbors then returned to their respective homes, feeling sad at heart. Some had not yet reached their homes, when the news was brought that the lost had been found. The large dinner bell was then rung, the signal in case any discovery was made. The crowd reassembled to learn the news. The particulars, as your correspondent learned them, are as follows: Mrs. Kalbfleisch was overtaken on Friday evening by a heavy rain storm, and not wishing to get wet, entered the spring-house of her brother, Irvin Younkin, about two miles distant. A short time after a young man in the employ of Mr. Younkin locked the door of the spring-house, not knowing any one was in. She was compelled to remain there until discovered by Mrs. Younkin, on Sunday evening. Mr. Younkin desires me to state that he returns his most sincere thanks to his neighbors and friends who so kindly aided in the search for his daughter.

Sarah Jane lived another three decades years after the incident. She died in October 1914 at age 54. burial was in the Younkin Cemetery in Paddytown. In a flowery obituary common for the era, the Meyersdale Commercial said:

She passed away so calmly and quietly into the Great Beyond. She closed her eyes upon the earthly things with confidence that she would open them on the glories of Heaven. She has been a member of the old Bethel Methodist Episcopal Church at Paddytown, since her early youth. Her falling asleep has removed from the midst of her family a devoted wife, a loving mother and her influence remains as an inspiration to those who knew and loved her; as her hopes were bright those left behind feel that they have only parted with her temporally and to meet her again, where the sun never sets and the leaves never fade.

|

|

|

Lazear Cemetery |

~ You Can't Die Happy 'Til You've Been to the Jacktown Fair ~

I’ve never attended the Fair, though my great-great grandparents lived there in the 1870s. But good ol’ Charles L. Younken – son of Yankee John Younkin and Polly Hartzell – went to the Fair, and then died, unusually. In the early 1850s he began a habit of drinking to excess. His consumption of liquor apparently increased, and he became violent and threatening to his family on his binges.

Said the Washington (PA) Review, he "has time and again threatened to kill different members of his family; at one time shooting a hog that he mistook for his wife, after night. His neighbors and friends bear testimony that he was a kind friend, a good neighbor and an honest man, when not in liquor."

In the fall of 1872, Charles went on another binge. The Waynesburg Republican reported that he had attended the Jacksontown fair on Sept. 12-13. Then this happened:

|

|

|

Greene County, PA |

...returning Friday evening to his home, drunk, Mr. Younken threatened to kill his wife, but his son Thaddeus watched him all night and prevented him from so doing. Saturday morning he went off and procured a pint of liquor, returning home and again abused his family. In the after part of the day he went to the barn and lying down went to sleep. Thaddeus said to his mother, he would go and kill a squirrel; that his father was asleep and could not harm her until he came back. When he came back his father had been beating his mother with a dipper, and dropping the dipper he seized a poker and swore he would kill her inside of three minutes. Just then Thaddeus entered the door with a rifle in his hands, returning from hunting, raised it and shot him dead, the ball entering about two inches behind [sic] the right ear, taking its course toward the left temple, remaining in his head. This is one story; and another is that the father was sitting in a chair sleeping when the boy returned, and he (Thaddeus) learning that his father had been beating his mother in his absence, deliberately shot the old man dead.

~ Kissin' Cousin Marriages ~

In the opening scene of the film

Gone With the Wind, the ravishing Scarlett O'Hara is being wooed by two lovestruck men on the porch of her home, Tara. One of them gossips that their friend Ashley Wilkes has become engaged to a cousin, Melanie Hamilton.

In the opening scene of the film

Gone With the Wind, the ravishing Scarlett O'Hara is being wooed by two lovestruck men on the porch of her home, Tara. One of them gossips that their friend Ashley Wilkes has become engaged to a cousin, Melanie Hamilton.

Scarlett pouts because she is secretly in love with Ashley Wilkes but has not told anyone. The suitor, not understanding Scarlett's disappointment, says that "The Wilkes and Hamiltons always marry their own cousins."

Later in the film, Scarlett confronts Ashley and demands to know why he is marrying Melanie. He responds, "She is like me, part of my blood, and we understand each other." Sound familiar? Many Younkins married their cousins too!

Ashley's response offer insights about why Younkins married their "kissin' cousins" in Southwestern Pennsylvania the 19th century. Although marriages of first cousins today are illegal in many states, they were commonplace then, especially in rural communities where clusters of families lived on adjacent farms and were of the same ethnic background and cultures.

I am descended from one such marriage -- Henry Minerd who married his mother's cousin, Mary "Polly" Younkin. Their son Ephraim married a cousin Joanna Younkin, and after her death, wed another cousin, Rosetta Harbaugh.

People of the 1800s had no knowledge of modern genetic research (which became a recognized science in the early 1900s), nor were there laws to prohibit intra-family unions. In fact, cousin marriages were considered to have value as a way to ensure that like-minded couples with similar values and heritage stayed together.

|

|

| In the film Gone with the Wind, Ashley Wilkes (played by Leslie Howard) marries his first cousin Melanie Hamilton (portrayed by Olivia DeHavilland) |

It may be surprising to learn how many noted couples were related. Among them were President Franklin Roosevelt; Albert Einstein; author Charles Darwin; poet Edgar Allen Poe; author H.G. Wells; the grandparents of President John F. Kennedy; and Pittsburgh department store owner Edgar Kaufmann Sr. who commissioned Frank Lloyd Wright to design their country home Fallingwater.

President Thomas Jefferson encouraged his daughters to "marry within the family." Martha married her distant cousin, Thomas Mann Randolph ... [and] Maria married John Eppes, the son of her mother's half sister. Today it all looks fairly incestuous, but no one then seems to have been in the least troubled by the inbreeding.

In the 1930s and early '40s, Charles Arthur Younkin of Charleroi, PA and Otto "Pete" Younkin of Masontown, PA, both of whom also were double Younkins, conducted and published their research findings which document many specifics of this practice. Quite fascinating.

~ The Hangman Always Hangs Twice ~

|

|

|

Albert

Hauenstine's hanging for cold-blooded |

Albert E. Hauenstine was born in 1864 in Ohio, the son of Lucinda (Dull) Hauenstine and grandson of Christina (Younkin) Dull. As did his siblings, he migrated to Nebraska in the 1880s and settled in Custer County. There, he taught in a very small sod school building and was married to a 17-year-old bride. Albert has been described as standing "about 5 feet 9 inches high, light moustache, very thin, light hair and light complexion, left eye a little crossed and looks towards the right; weighs about 140 pounds."

In the fall of 1888, it was rumored that Albert had broken into the farm house of a man named Batchelor. At about this same time, a clock and other objects went missing from the school where Albert taught. Two school board directors went to his home, confronted him and spied the missing items. In a panic, Albert shot and killed both. Albert then hid the bloodied corpses under a pile of hay, and skedaddled in a buggy.

The corpses were found several days later. "Owing to the fact that it is forty or fifty miles across the country to the county seat," noted the Omaha Daily Herald, "the sheriff will be a week behind the murderer in the pursuit."

The State of Nebraska offered $400 reward for Albert’s arrest. He was captured, put on trial, found guilty and sentenced to be hanged. On the scheduled day, several hundred spectators came to the courthouse in Broken Bow to watch. But Governor Boyd announced that the hanging would be postponed so that Albert’s sanity could be examined. Albert admitted to the sheriff that "there were times when he was not right but that most of his actions had been feigned.”

Eventually, Albert was deemed sane, and the second appointed day of execution was rescheduled to May 23, 1891. Crowds assembled, and tickets were issued for a small number of people to view close-up, the rest behind a fence. Crowds surged toward the scaffold. Albert was brought up the steps and made a final statement: "Gentlemen, I am very sorry for what I have done, and for the trouble I have made you. I hope you will take warning by what I have done. Remember little things sometimes come to great things. I ask for your forgiveness."

|

|

|

Albert's execution day, courtesy Library of Congress American Memory Project |

At the moment Albert the trap door was pulled, the rope snapped, and he fell gasping and groaning to the ground below," reported the Columbus (NE) Journal. "A new rope was secured, and sheriffs of other counties, present to learn something of executions, hustled Albert up the scaffold once more, where his pinions were again adjusted and the new rope placed about his neck.

This time the body dropped and made a sudden jerk which left no room for doubt that the second trial was successful. The body was left hanging even after physicians pronounced him dead. The crowd waited even longer, and, said the McCook Tribune, "the expression of grim satisfaction at the vengeance dealt out to the murderer was general." The sensational news was published far and wide, and an 8-inch by 6-inch mounted sepia-toned photograph of the hanging was sold as a novelty.

~ Death on the Rails ~

|

|

|

Keystone Courier, 1887 |

This the sad tale of Sarah (Tannehill) Younkin, widow of Devil Jake Younkin. In 1887, she lived near Connellsville.

At that time, three of her adult sons were railroaders. Son John was married and had children. He worked as an engineer with the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad. In Jan. 1887, was killed in an accident in the yards of Hyndman, Somerset County. His remains were brought back to Connellsville for burial in Hill Grove Cemetery. The Connellsville Keystone Courier reported that John had had:

... several hairbreadth escapes on the Connellsville division, but his usual luck deserted this time. A westbound freight, due at Hyndman at 2 o'clock last Friday morning, arrived behind time, expecting to run into the siding there and clear the track for the eastbound Baltimore express. But the east end of the siding was blocked with cars and the freight train was compelled to run on and back in at the other end. This consumed all its margin of time. The train had barely gotten into the siding when the express came thundering down the mountain at the rate of thirty miles per hour. In the hurry and excitement the flagman either neglected to close the switch or did not have time to do so, and the flying passenger train ran into the siding and collided with the freight. Younkin, the engineer, attempted to get off his engine, and had swung himself to the steps, but he was too late. Before he could jump, the engines came together with a tremendous crash, throwing him violently between his engine and the tender. While in that position, the rebound of the cars crushed his hip and injured him internally.

Eight months after the accident, while on her way to place flowers on her son’s grave, Sarah decided to take a shortcut near Gibson Station, rather than climb a steep hillside near the track. Tragically, a moving locomotive, which was transporting the U.S. Mail to Baltimore and Washington, DC, came round the curve which Sarah did not see until it was too late.

Reported the Courier:

The train left the depot on time. As it neared Gibson station, the quick, jerky 'hoot! hoot! hoot! of the locomotive whistle, as the train flew along, was the signal for every passenger's head to be poked out of a window. A great many people in town heard the signal and knew that someone was on the track. But those on the train and at the station soon knew that an old lady had been struck and killed.

|

|

|

Connellsville's Hill Grove Cemetery |

Her broken remains were placed at rest in Hill Grove Cemetery, and a coroner's inquiry pronounced the senseless death as an accident. Hill Grove records show that while the son has a stone, she does not.

The tragedy so touched the public’s interest that for years afterward, at 10-year-anniversary increments, a short summary was reprinted in the Connellsville Daily Courier and also in 1937 in the Younkin Family News Bulletin. Many decades later, Jacob and Sarah were mentioned by name in a 1963 edition of the Laurel Messenger of the Somerset Historical and Genealogical Society.

~ The Meaning of Suffering? ~

|

|

|

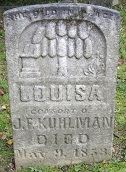

A young

mother's grave, |

I’ve long wondered what pain and hardship has had to be endured by each of our particular set of ancestors for any of us to exist. What wars and armistices, upheavals, betrayals and tragedies and much more had to occur – for each generation to have been in the right place at the right time on the right day for us to have been conceived?

Was extreme heartache necessary in some circumstances over the continuum of time and space? It’s exceedingly humbling to think we should be so important.

Here are just two tragedies that occurred in my own family tree, without which I myself would not have come into being:

Great-great grandfather James C. Cain lost his first wife, Rachel Ann Reid, after just four and a half years of marriage. She died from a bad cold at the age of 22, leaving him with four young children. His second wife, Margaret Ellen White, was my ancestor and together they produced my great-grandmother, Armena Viancy (Cain) Miner. If the first wife had not died, the second marriage would not have taken place.

Great-great grandfather Madison Ullom also lost to premature death his first wife, Sarah Gray. She passed at age 34, leaving behind four children under the age of 10. His second wife, teenager Melissa Ann Hupp, was my ancestor, and their son Lantz was my great-grandfather. The death of the first wife was necessary for this chain of interlinked events to happen.

|

|

|

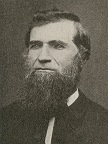

Rev. J.F. Kuhlman |

So this last story is about Rev. John Frederick Kuhlman, husband of Louisa Smith and son in law of Garrison and Hannah (Younkin) Smith. Frederick and Louisa were married in about 1849 or 1850. They had two known sons -- Dr. Winfield Kuhlman and Rev. Luther Kuhlman. Tragedy rocked the family in May 1853, when Louisa died at the age of 20, apparently in childbirth with a third baby. One can only imagine how her husband, a religious, God fearing man, pleaded and begged the Lord to save her life. But it was not to be. She was laid to rest in the Younkin family graveyard – the Lemmon Farm – with an elaborate stone carved to mark her final resting place. At the top was inscribed these words, "She died in peace."

The two sons were separated and taken into the homes of their grandparents, Winfield with the Smiths and Luther with the Kuhlmans. Frederick did not remain unmarried for long. He wed again to Rachel Rush, daughter of "Squire" Jacob and Rush and Ruth Scott of Somerset County.

In June 1864, Frederick received an exceptional and challenging assignment in Nebraska. His objective was to make a preliminary assessment of the Lutheran Synod's efforts to minister to pioneer families and create local churches. After making the long trip by river and wagon, he first preached at Immanuel Church in Omaha. Then he traveled by stagecoach to Fremont, walking the final 9 miles to the town of Fontanelle. Among his stops were two German settlements near Fontanelle and the town of West Point. He returned home to Pennsylvania and, after being offered a more permanent assignment in Nebraska, accepted the call and left Pennsylvania with his wife and children in September 1864, while the Civil War raged elsewhere.

For the next 18 years, Frederick served as a missionary in Ponca and Fontanelle on the outskirts of Omaha. Then his second wife died.

Leaving Nebraska in the early 1880s, perhaps in grief, Frederick returned to Somerset County and made his home in Jefferson Township. While there in 1882, he was appointed pastor of the Mount Zion Evangelical Lutheran Church. He then served as pastor of the Mount Calvary Lutheran Church of Lavansville, and translated from German into English the old Samuel's Evangelical Lutheran Church records dating to 1791. A parishioner, Andrew Frankforter, once said that he had a great deal of affection for Frederick "in that he could read for him from his German bible which he prized so highly." He returned to Nebraska, and in 1889 or '90 served in Kansas with the Zion's Evangelical Lutheran Church.

Heartache of a different sort rocked Frederick's world in June 1899, a time when he was residing in Martinsburg, Nebraska. A cyclone blew in and swept away his home. His son Luther, then serving as pastor of a church in Frederick, MD, was granted leave to go west to his father’s aid, and the congregation took up a collection of funds.

Having fought the good fight, having finished the course, having kept the faith, Frederick died at the age of 97 on in 1926 in Lincoln, Nebraska, far away from the Lemmon Farm here. A obituary in the Lincoln Star included his photograph and noted that he was not only "Nebraska's oldest Lutheran minister" but that "a large delegation of former parishioners is expected to attend."

At least six of the Kuhlman offspring and spouses became physicians, and five entered the clergy. All this after the death of a first wife, a tragedy which at the time seemed senseless. In retrospect, the suffering seemed to be almost necessary for all of the good work that followed in so many countless lives where souls were saved and bodies healed. It makes one think deeply about pain and loss, and our ability to be mentally tough in the face of great difficulty. If you’re a person of faith, you might say that God knew what was happening, and was in control.

Copyright © 2015 Mark A. Miner