|

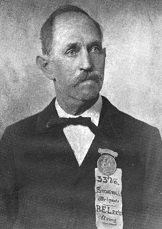

Jeremiah Minard |

|

|

Fairmont Cemetery, Newark, NJ |

Jeremiah Minard was born in about 1841 in the mountains of Preston County, VA (later WV), the son of Burket and Susan (Hartzell) Minerd.

He is one of just two cousins in the extended family to join the Confederate army during the Civil War, serving under Stonewall Jackson in some of he early war's bloodiest battles and witnessing the creation of the "Rebel Yell." After crushing slaughters, hunger, exhaustion, desertion, arrest and imprisonment in harsh conditions, he took an oath of allegiance to the Union and switched sides. Now fighting with a Union regiment, he was wounded three times and later drew a federal pension for his service while descending into disability and madness.

At age nine, when the 1850 U.S. Census was enumerated, Jeremiah was listed with his parents and siblings on a farm in Preston County, then part of Virginia's northern tier. By 1860, his parents had separated, and his siblings were scattered in other homes.

Jeremiah's own whereabouts in 1860 have not yet been found, but are being researched.

He stood 5 feet, 7½ inches tall, with a fair complexion, grey eyes and dark brown hair, and wore no whiskers.

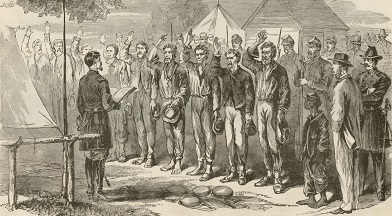

~ Joining the Confederates' 33rd Virginia Infantry and Stonewall Jackson's Brigade ~

|

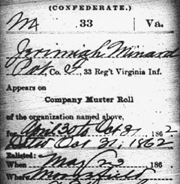

Jeremiah's Confederate muster |

As he reached adulthood, Jeremiah was acutely aware of the growing tension and divided loyalties in his home state of Virginia over the looming specter of civil war. When the War Between the States finally broke out, in April 1861, he was 20 years old and an able-bodied man capable of military service.

With other states having seceeded from the Union, the commonwealth of Virginia was faced with a go or no-go decision. Spirited rallies and meetings were held and newspaper articles written on both sides. Political delegates from northwestern Virginia convened in Wheeling. In April, Fort Sumter in South Carolina was attacked and surrendered.

On May 23, the voters of Virginia took to the polls. In Preston County, only 63 of 2,319 voted to secede. But overall, Virginia chose secession. Union troops immediately marched from Parkersburg and Wheeling to try to control Preston and other northern tier counties. Confederate forces in nearby Grafton, Taylor County were rumored to be en route to arrest and hang Union supporters in Kingwood.

Jeremiah already had made up his mind. On the very day of the referendum, he enlisted in the Confederate army as part of a Preston County regiment. From there, he traveled to Moorefield, Hardy County, about 77 miles to the southeast of Preston County, and was assigned the rank of private in the 33rd Virginia Infantry. He was placed within Company F and agreed to served a term of one year. Company F popularly was known as the "Independent Greys" or the "Hardy County Greys."

Another of his cousins from Preston County, Presley Martin, also joined the Confederate military -- the two known "rebels" in an extended old Pennsylvania-German family which sent more than 180 soldiers to the Civil War.

Jeremiah's brother-in-law, James K. Martin, enlisted in the Union Army in March 1862 as the first anniversary of the war neared. He was made a member of the 3rd Regiment, Potomac Home Brigade, Company H. So was Jeremiah's cousin, Frederick Pringey, son of Joseph and Margaret (Younkin) Pringey. What the interpersonal relationship was between Jeremiah and his sister's husband and cousin likely will never be known.

In Jeremiah's military service papers, on microfilm today at the National Archives in Washington, DC, his first name is spelled "Gery," "Jerimiah" and "Jeremiah."

|

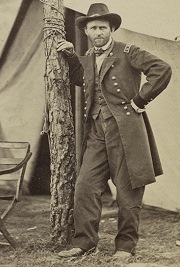

Stonewall Jackson |

~ The 1st Battle of Manassas/Bull Run and the Birth of the "Rebel Yell" ~

The 33rd Virginia officially became part of the "Stonewall Brigade" on July 15, 1861 under the command of Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson who arched to great fame early in the war. Just a few months earlier, in April 1861, Stonewall had been a professor of artillery at the Virginia Military Academy, and, upon the outbreak of armed conflict, had led his cadets into the Confederate ranks. The other units in the Stonewall Brigade were the 2nd Virginia, 4th Virginia, 5th Virginia and 27th Virginia Infantry regiments.

Virginia Polytechnic Institute professor James I. Robertson Jr., author of The Stonewall Brigade, says that the Brigade "achieved a reputation almost without parallel for agility, gallantry, and pugnacity."

On July 21, 1861, less than two months after enlisting, Jeremiah and the 33rd Virginia joined a battle along Bull Run Creek, near the Manassas Junction railroad facility, about 25 miles from Washington, DC. They were still poorly trained, but so were their opponents. Local citizens knew a fight was brewing, and hundreds traveled out in buggies and carriages, carrying picnic lunches and binoculars, to watch what they hoped would be a real battle. Most believed naively that rational minds on both sides would bring the war to a close once they got a battle out of their system. They were horribly wrong.

|

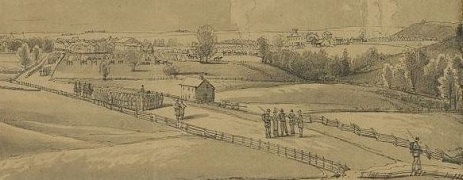

33rd Virginia Infantry |

The First Battle of Bull Run/Manassas is said to have been the first time that the Brigade saw Jackson as a fierce warrior rathan than an eccentric academic. That morning, when Jackson saw that the Union Army was beginning its assault toward his troops, in the vicinity of Henry Hill, he simply said "Good, good."

Jefferson Davis, President of the Confederate States of America, was on-site that day.

Commanded by Col. Arthur C. Cummings, the 33rd Virginia was on the far left of Jackson's battle line. He knew his men were "undrilled" as well as "raw and undisciplined." They spent the morning forming unnoticed in the woods as battle raged elsewhere on Henry Hill. When told that his troops were faltering, Jackson simply said, "We will give them the bayonet."

Then in the early afternoon, after being pushed down a hill toward Sudley Road, Union troops then counter-attacked. A 5th U.S. Artillery battery, among them the 11th New York commanded by Captain Charles Griffin, directly faced the 33rd from a distance of several hundred yards. They began to march forward, supported by two large cannons.

The New Yorkers' goal was move to the left of the Confederate artillery line and shell it from a perpendicular angle, known as "enfilade" fire. They mistook the nearby 33rd Virginia's men in the woods as friendly forces and so ignored them as they shelled. As he realized his opponent's mistake in judgment, Cummings ordered the 33rd Virginia to wait to charge until the enemy got closer of their line, although he feared that his green troops were not quite disciplined enough to hold back for long enough.

Manassas battlefield sign today |

At about 3 p.m., the 33rd Virginia were ordered to strike. They advanced to within 40 paces of the guns and fired. But in doing so initially, surpsingly, they did not aim their guns directly at the enemy, but rather upward at a 45-degree angle. An eyewitness with the 2nd Virginia was deeply disappointed with this volley, knowing it would not do any harm. But the 33rd pushed ahead across the open field and seized the guns. Wrote author S.C. Gwynne in hisbestseller Rebel Yell, "It was the first Confederate victory of the day. Cheers went up as the members of the 33rd, many of them merely boys just a month or two from the plow handle and mechanic's shop, exulted." Two plaques on the field today mark these spots as "Point Blank Volley" and "Turning the Tide."

But the 33rd Virginia's elation was short-lived, as the 14th Brooklyn/New York Infantry began a counter move with heavy fire of its own. One of the men said that the 33rd was "cut to pieces." Jeremiah and his mates fell back from their prized captured cannon, crumbling, collapsing, with about one third of the men going down.

But Jackson was not yet done with his Brigade. He ordered two regiments to the 33rd's immediate right, the 4th and 27th Virginia Infantry, to press forward and make a "scream of the furies" at the top of their voices. Their scream was blood-curdling to the enemy's ears, a high-pitched screech and a yelp described as inhuman, unearthly, wild animal-like. It was the very first time it was heard. With this ungodly sound now unleashed, the rebels advanced on the Union batteries on Henry Hill and penetrated the center of the enemy's line, now widely known as the "Rebel Yell."The Union forces retreated for good, sealing their fate for the day.

|

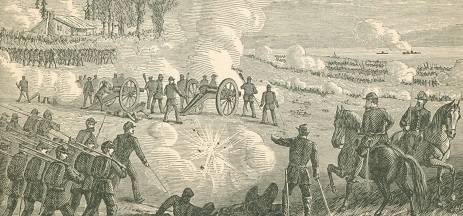

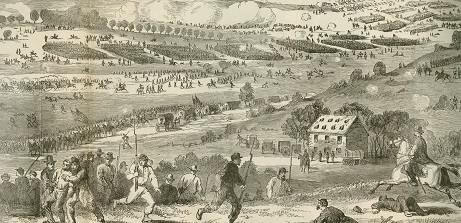

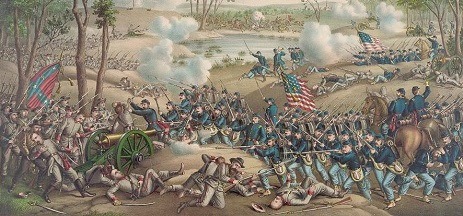

Above: the 33rd Virginia aboard the Manassas Gap Railroad en route to 1st Manassas/Bull Run. Courtesy Google Books. Below: the 33rd Virginia repelled repeated Union charges at Manassas but suffered 1/3 losses. |

|

|

John O. Casler, 33rd Virginia |

Upon hearing the news, President Abraham Lincoln "listened in silence, without the slightest change in feature or expression" and walked away, wrote biographer Carl Sandburg,

While Jackson's army thus won the first major battle of the Civil War, it came at a steep cost. The 33rd Virginia lost 183 men killed and wounded, perhaps one-third of its men, a staggering number, but had established a reputation for aggressive soldiership.

Private John O. Casler, of the 33rd Virginia's Company A, later recalled the debris on the battlefield, along the line of the Union's retreat, as he saw it a few days later -- "The whole country was strewn with broken guns, cartridge boxes, canteens, cannon, caissons, broken wagons and the general baggage of the army," he wrote in Four Years in the Stonewall Brigade, widely considered one of the very best memoirs authored by a private soldier in the war.

Wrote Geoffrey C. Ward in his book The Civil War, An Illustrated History, the rebel yell "first heard that afternoon ... would eventually echo from a thousand battlefields."

~ A Cruel January in a Western Virginia Outpost ~

Jeremiah and his comrades saw no further action that year, but moved into a winter camp along the Pughtown Road near the Virginia town of Winchester. Robertson's book The Stonewall Brigade says that a number of the men were restless and pining for home, some "feigning illness" to try to earn a furlough. Some just left camp without permission, an act known as a "French furlough." In November, a wave of measles and the flu -- dubbed the "Virginia quick-step" - swept through the unit.

Then on New Year's Day 1862, without telling anyone about his plans (which was his habit), Jackson ordered the Brigade on a long march to capture the town of Romney, Hampshire County, VA (later WV). The men were not issued tents, blankets or overcoats as protection from the mountain cold. Jackson pushed his miseried soldiers without relief, and punished one officer for stopping so his men could eat their rations. Horses, wagons and reinforcements stalled. Blistered by the ice, snow and chill wind, men died of frostbite or were injured for life. Author Gwynne calls it "the most horrific noncombat experience of the war."

The Brigade took two weeks to march through Berkeley Springs, VA and Hancock, MD and arrive at Romney, only to find that 7,000 Union troops had abandoned the town. Jackson wanted to push further into western Virginia and Maryland to make additional conquests, but his regiments were spent. Bitter soldiers derided Jackson's judgment and cursed his name. They began to realize that they were individually expendable, a commodity not as vital to the wartime cause as they had believed.

|

Romney, VA (now WV), occupied during the Civil War. Library of Congress |

In early February, the Brigade returned to Winchester, having marched a total of 100 very hard miles. One regiment was left behind in Romney, but it, too, eventually left. The town would change hands 56 times during the war. Once back in Winchester, Jackson's men continued to express anger at being so used. There were more desertions.

Jeremiah survived the Romney campaign but no doubt was the worse for the experience. He received a furlough on Feb. 15, 1862 -- but whether he returned home to family is unknown. That same month, his enlistment period was extended for the duration of the war. Wrote James M. McPherson in For Cause and Comrades, "there was no such thing as a Confederate short-timer. The Richmond Congress required men whose enlistments expired to reenlist or be drafted." In April 1862, the 33rd Virginia was called upon to "forcibly" chase and round up men from other regiments who had refused to comply.

~ Heavy Action in Jackson's Valley Campaign~

On March 23, 1862, despite the fact that their regiment was down to between just 150 to 200 men, Jeremiah and the 33rd Virginia saw their first action of the new year. They fought at Kernstown, near Winchester. Led by Brigadier General Richard B. Garnett, they were placed behind a stone fence, sandwiched between Cedar Creek Road and Middle Road. Both sides exchanged murderous fire. Some 53 men of the regiment were killed, wounded or captured, many suffering "horrible" head wounds from Union minié balls. Wrote Gwynne, "Many soldiers later commented on the enormous sound of war: it was more of a giant, rolling roar than a succession of shots."

The outcome of the Kernstown battle was mixed. Some said it was a victory for both sides, tactically for the Union and strategic for the Confederacy.

After Kernstown, Jackson drove his foot soldiers hard for the next two-and-a-half months. His plan was to use speed, misdirection and surprise to prevent Union forces from occupying the Shenandoah Valley, even though the South had fewer men. It was dubbed the "Valley Campaign," and Jackson's magic was to outrace the enemy to strategic sites and achieve smashing surprise attacks. In 39 days of actual marching, the men covered 555 miles, averaging 14 per day. During that time, in about April, Jeremiah is alleged to have been promoted to ordnance sergeant, although that is not reflected in his regimental papers.

Most of Jackson's armies saw significant action at McDowell on May 8, Front Royal on May 23 and Cross Keys on June 8. The 33rd Virginia, however, did not receive orders and did not participate until late.

|

Malvern Hill battlefield near Richmond |

The 33rd Virginia fought at Gaines' Mill on June 27, said to have been Robert E. Lee's most sizable attack of the entire war. It pitted 32,000 Confederate soldiers against the Union's 34,000 in the quest to occupy swamps and bluffs. The evening's back and forth of shooting was so deadly that some compared it to butchery or carnage. The rebel yell was in full volume, sounding to one observer like "40,000 wildcats." When a Confederate charge broke through and captured heavy guns, the Union retreated. Total casualties that day were 9,000 Confederate and 6,000 Union.

Then again, at Malvern Hill on July 1, the 33rd took part. One general remarked that the battle produced the "most terrific fire" he had ever witnessed. The Union deployed a pounding bombardment from batteries of 268 cannons and siege guns. Confederate General James Longstreet tried to dislodge the heavy guns with his own counter-fire, with small effect. The Confederate infantry was not ordered to attack the enemy's overwhelming stronghold until late in the day. And they were cut down in masses. Rebel losses were 6,650 and Union 3,007. One Union officer later wrote that there were so many grey-clad wounded on the ground, writhing and shifting, that it gave "the field a singular crawling effect." Confederate commander D.H. Hill -- Jackson's brother-in-law -- bitterly called the engagement not "war" but "murder."

During Malvern Hill, the headcount of men in the 33rd dropped to 129, with Jeremiah included. The troops then established a camp at Gordonsville and spent three weeks there resting. Writing in The Stonewall Brigade, Robertson said that regimental physicians had conferred and decided that the brigade, suffering from badly worn feet, diarrhea and exhaustion, was "physically unable to endure much more activity."

The men of the 33rd spent that Fourth of July holiday picking blackberries. Upon coming across a band of Union soldiers doing the same, they called a truce for the day, visiting and trading for rare treats such as newspapers, coffee and tobacco.

At Cedar Mountain/Slaughter Mountain on Aug. 8-9, the 33rd Virginia again saw battle action, hoping to stop Union General Pope's expected advance on Richmond. Aligned parallel over a two-mile stretch of pasture and field, 15,000 rebel troops well outnumbered the Union's 9,000 under the command of Nathaniel Banks. During the first day, Jeremiah and the Stonewall Brigade were on the far left but not yet called to the front.

"The day was hot," said Casler of the 33rd Virginia, "and several men dropped dead in ranks from sunstroke." The next day, both sides faced an exchange of heavy shell and cannon fire for the first several hours. The 33rd formed a line in the woods. Casler said that "We had not been there long before the artillery opened out on both sides and shells rattled through the woods over our heads very lively." But when the men of the 33rd were not aggressive in advancing at one point, an officer ordered its flag-bearer to climb over a fence and begin to move, rightly believing that the rest of the regiment would follow.

As Banks' Union troops commenced an attack, the Brigade was ordered forward. Banks found an opening in the rebel line and pushed through. Seemingly on the edge of defeat, Jackson mounted a counter-attack and was at the very center of combat, the air filled with the hideous screech of the rebel yell. Confederate cavalry under Gen. A.P. Hill joined the charge and forced the Union men to retreat. "We had severe fighting for a short time, when the enemy broke," Casler said. "We pursued the enemy two miles, until dark, and lay in line all night. At one time we received a shower of shells from the enemy, but we did not reply."

In just 90 minutes of very difficult fighting at Cedar Mountain, the Southern casualties were 1,338 and the Union's 2,353. The 33rd's surviving soldiers were thoroughly spent, exhausted beyond anything they ever had known.

~ Harsh Camp Discipline ~

|

Soldier punishments in the Stonewall Brigade, left to right: forced to wear a "barrel shirt" for being AWOL and returning drunk - tied up by the thumbs - bucked and gagged - carrying a heavy rail for 8 hours under guard. Google Books |

Jackson was a strict disciplinarian, as were his Brigade Generals William Taliaferro and Charles S. Winder. They tolerated no misbehavior, most especially for absences without official leave and desertion. Jackson convened a court martial after the Battle of Cedar Mountain and sentenced deserters to death by execution. He only held off in doing so for fear of a public backlash. Three others were shot by Taliaferro's firing squad in mid-August. Winder's form of discipline was different, focusing on humiliation.

When 30 men defected in July, Winder had them hunted down. He then marched his recaptured troops "into the woods, their hands bound at their wrists, their arms slipped over their knees and a stick placed beneath the knees and above the arms," wrote Lowell Reidenbaugh in 33rd Virginia Infantry. When learning of the form of punishment, Jackson had it stopped. But the soldiers' deep anger toward Winder remained. Some dark rumors within camp hinted that he might become the target of friendly fire. In a twist of fate, Winder was killed by an enemy shell at the Cedar Mountain on Aug. 9. One can only imagine what toll all of this must have taken within Jeremiah's psychology and emotions.

In mid-August, four soldiers from the Brigade deserted, were captured and brought back into camp. Jackson ordered their execution by firing squad. As the wrongdoers knelt blindfolded beside open graves, they were shot and killed. Wrote Robertson, "Officers then marched their regiments past the graves, to impress indelibly upon them the awful consequences..."

~ A Far Bloodier Second Battle of Manassas/Bull Run ~

In August, capping three days and nights of hard marching, with only four hours sleep total, the 33rd Virginia returned to the Manassas railroad junction, scene of their earlier fight. To their joy, the men discovered abandoned Union storehouses and helped themselves to the spoils, including quantities of food and drink. They also raided Union railroad cars for tents, blankets, clothes and medical supplies.

Then on Aug. 28, the regiment fought again at Manassas, near the Brawner Farm, in intense summer's heat. Jeremiah may not have known, although he might have imagined, that a handful of his cousins on his father's side were among the enemy. Among them were Levi Miner of the 11th Pennsylvania Infantry, Heley Patrick Cross of the 2nd Maryland Infantry of the Stiles Brigade and Henson Smith Liston of the 3rd West Virginia Infantry, Milroy Brigade.

The 33rd Virginia directly faced the 2nd Wisconsin Infantry, and was the target of a swarm of bullets, protected only by an old fence. Casler recalled later that the men would "lie down, load and fire, and it seemed that every one who would raise up was shot. We lost severely" on the first day. Famed Confederate General Richard "Dick" Ewell lost a leg. Day two was quieter, with skirmishing back and forth. That evening, virtually everyone attended the Brigade's prayer service, organized in part by Jackson.

|

Above, 2nd Manassas/Bull Run, where 18,300 Union and Confederate soldiers were killed or wounded, and after which Jeremiah deserted. Below, the narrow stone bridge at Manassas clogged by retreating Union, thus blocking a pursuit. |

On the third day of battle, on Aug. 30, the men of the 33rd took a position in an unfinished large earth excavation for a future railroad line. Wrote Casler, "My brigade was in a small cut, with a field in front sloping down about four hundred yards to a piece of wood. The enemy would form in the woods and come up the slope in three lines as regular as if on drill, and we would pour volley after volley into them as they came; but they would still advance until within a few yards of us, when they would break and fall back to the woods, where they would rally and come again." When ammunition ran low, the 33rd's soldiers used the butts of muskets, bayonets and even rocks in hand-to-hand combat. One man after another went down trying to bear the colors. After the third Union assault, wrote Casler:

... as they broke, we were ordered to charge, and as Longstreet's corps had turned their left, our whole line charged, and the rout became general. But the stone bridge over Bull Run became blocked up with artillery and caissons, and we could not cross with our artillery; and as it was getting dark, this put an end to the conflict.... It was a terrible battle, and both sides lost severely. The slope in front of us was covered with dead, dying and wounded; but my brigade lost but few, as we were protected by the railroad.

Against increasing odds of attrition, Jeremiah once again survived without injury. But 105 of his colleagues in the 33rd Virginia were killed or wounded, among them 24 dead and 91 wounded. Second Manassas had cost some Southern regiments seven out of every 10 fighting men. Overall Union killed and wounded were 14,462 and for the Confederate army 11,739. It was, by far, the bloodiest battle of the Civil War up to that time, and exceeded casualties from First Manassas/Bull Run by a factor of more than five.

Casler wrote that after "the battles of Manassas I found myself completely used up. I had slept but little for six days and nights, and was suffering with sore feet and hemorrhoids."

The farms of Manassas were strewn with the mangled, dying and dead, far more than could be removed and decently buried. Two winters later, Jeremiah's cousin David Harbaugh and the 5th Pennsylvania Heavy Artillery labored at the battlefield, burying the rotted skeletons of thousands of dead soldiers which had lain exposed and unattended ever since.

|

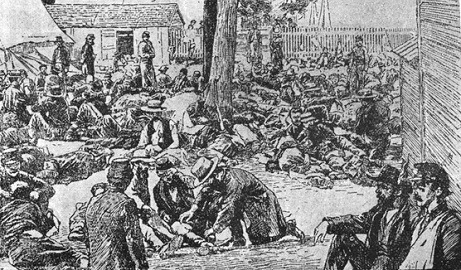

The Stonewall Brigade's field hospital after Second Manassas/Bull Run |

~ Desertion, Arrest and Charges of Spying ~

|

Wheeling Intelligencer, Oct. 18, 1862, |

After Second Manassas, General Robert E. Lee and Jackson decided that their next movement should be a push into Union territory rather than a defensive fallback to Richmond. Many of the Brigade soldiers, who had been willing to lay down their lives to protect their home soil of Virginia, did not feel the same. Scarred, barefoot, hungry, unbathed and raggedly dressed, they were repulsed by the idea of making an offensive into neutral Maryland.

Hundreds if not thousands abandoned their camps and colleagues and went home. Jeremiah himself had had enough. He walked away from his ordnance train and joined the mass desertion. On Sept. 2, 1862, he was reported absent without official leave and later officially was declared AWOL. There is no evidence that he had any other motive in his departure.

Jeremiah made his way by rail and by foot to Virginia's eastern panhandle near Maryland. He somehow came into possession of the clothes of a man whose family home had been burned in a recent rebel raid. He finally was captured after a month on the run. His arrest made news in the Wheeling Intelligencer. Under the headline of "A Spy and a Deserter," on Oct. 18, 1862, the Intelligencer reported that:

On Thursday evening two men named Jeremiah Minard and Leander D. Lowry, were brought in from New Creek and committed to the Atheneum. The evidence against Minard goes to show that he is a spy. He was first arrested by Adam Since, a citizen. At the time he had upon his person clothing which Since recognized as belonging to his son and which were lost when the rebel burners destroyed Mr. Sine's house by fire. He represented that he was an Ordinance Sergeant in the rebel army. After the battle of Manassas he deserted, and making his way to Gordonsville took the cars for Stanton and made his way over the hills to Moorefield. He said he was on his way to New Creek when arrested. Minard was taken to New Creek. On Monday last he escaped from the guard house but on Tuesday he was arrested by Jeremiah Roberts, a Union scout. Roberts made Minard believe that he was one of Imboden's men when Minard freely confessed that he was a spy and had been to New Creek. He described the condition of things there and said if he had had an opportunity he would have blown up the magazine of the fort.

|

Mountains near New Creek (Keyser), WV where Jeremiah was captured |

|

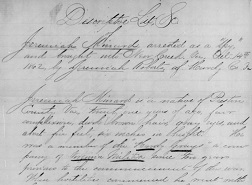

Union Army report labeling Jeremiah |

Jeremiah told his captors that his home was in Nobbley, Preston County. In an official report to superiors, Edward C. James of the 106th New York Infantry, responsible for holding the prisoner, wrote that "It was hinted at the time [of capture] that Minard was here for the purpose of a spy, and that he belonged to Imboden's men.... Minard is undoubtedly a bona fide spy, and we only regret here that it is not in our power to deal out to him the punishment he so justly merits." James then went on to detail how Jeremiah had been brought in:

Last Monday morning he was missing from the Post Guard House and although search was made could not be found. No further newes was heard from him until near Tuesday noon when he was brought in by Jeremiah Roberts of Hardy Co., one of Abijiah Dolly's Union scouts. He had been re-srrested at the house of Abram Roderick's some twenty miles from New Creek, Va. Roberts, by representing to Minard that he (Roberts) was one of Imboden's men, induced him to accompany him. Minard then freely confessed that "he had been to New Creek as a spy, that two thousand infantry properly supported could take the post, giving such information as he could relative to the strength and position of the forces, and adding that if he only had a fuse he could have blown up the Magazine of the Fort." He, moreover, induced a soldier to desert, when he went, and who has not yet been re-arrested. Roberts, having to Minard into his power, brought him in to New Creek again, and now by Gen'l. Kelleys direction he is sent to Wheeling. The witnesses in this care are Jeremiah Roberts, Abijah Dolly, Adam Sines, Cyrus Patrch and Philip Richmond, all of Hardy County.

~ Brutality of POW Life at Johnson Island ~

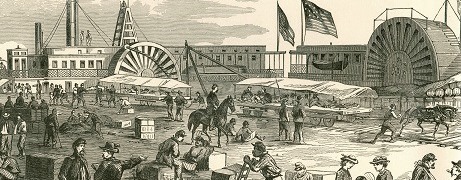

Confederate prisoners were only held a few days in Wheeling's Atheneum (also spelled "Athenaeum" and nicknamed the "Lincoln Bastille"), a converted warehouse and theater. From Wheeling, Jeremiah was transported to Camp Chase, a POW camp near Columbus, Ohio. It effectively could have been a death sentence. More than 2,260 prisoners died at Camp Chase from lack of nutrition and pneumonia, smallpox and typhoid fever.

But within a few days, on Oct. 21, 1862, Jeremiah was moved again to Johnson's Island, another Ohio POW camp three miles north of Sandusky along Lake Erie. He was present and accounted for in the prison records as of Nov. 25, 1862. One of these rolls gave his first name as "J.W."

Jeremiah remained incarcerated at Johnson's Island for more than a year. While he would have been familiar with severe winter weather from his growing-up years in the mountains of West Virginia and Maryland, many of his fellow POWs from the Deep South had never seen snowy gales. No one was equipped for temperatures reaching 25 degrees below zero.

In his article "Plain Living at Johnson's Island," published in The Century in March 1891, former prisoner H. Carpenter wrote tongue in cheek that the "sleeping arrangements consisted of bunks in tiers of three, each furnished with the usual army bedtick stuffed with straw, and far superior to the earth and ditch which had been our beds for months previous to our capture. The crowded condition of the prison necessitated that two men should occupy each bunk, which had the redeeming feature in winter that the occupants were sheltered by two blankets instead of one."

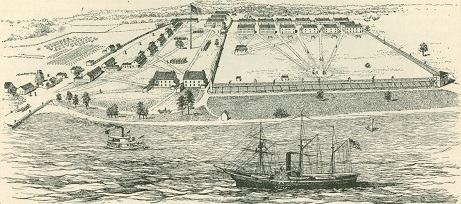

|

|

Above: shivering Johnson's Island POWs sleeping two to a bunk, covered by only a thin blanket. Below: view of the prison from a lithograph after a wartime sketch by Edward Gould, a soldier in the 128th Ohio. In the foreground is Lake Erie and the U.S. guard steamer Michigan. The long paths inside the enclosure lead from the prison blocks to water pumps. |

|

|

Freezing POWs at Johnson's Island |

Johnson Island's daily ration of food, Carpenter wrote, "consisted of a loaf of bread and a small piece of fresh meat... insufficient to satisfy the cravings of hunger, and left us each day with a little less life and strength with which to fight the battle of the day to follow." He added that:

The prolonged confinement had told severely on us, and the men could not but yield to its depressing influence. There was little to vary the dreary monotony that made each day the repetition of the day before and the type of the day to follow. This alone would have been sufficient, but when scant food and cold were thrown into the scale it is little wonder that both mind and body should yield under the constant strain.... It was generally known among us that some mitigation of our condition would be afforded such as took the oath of allegiance, and as this meant increased food and better clothing some few availed themselves of the offer.

Winter turned into never-ending tedium of spring, summer and fall. One can only imagine Jeremiah's emotions when, in early May 1863, he learned that Stonewall Jackson had lost an arm at Chancellorsville and had died.

After more than a year at Johnson's Island, and at the instigation of Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, Jeremiah was offered the opportunity to be set free. The condition? That he swear an oath of allegiance to the United States. Author Robert C. Doyle, writing in The Enemy in Our Hands, has stated that switching sides during the war was "not common" but "occurred regularly on a small scale" for prisoners who feared for the future of the fragile Confederacy. He cites one example at Johnson's Island, where a prisoner took an oath of allegiance, only to be beaten and shunned by other POWs. Union General Benjamin Butler called such soldiers "repentant rebels" - "whitewashed" - and "galvanized."

Jeremiah accepted the federal offer, and on Oct. 28, 1863, he took the oath. But his newfound freedom was not a complete released from military obligation. Just two days later, he joined a New York regiment

Information about Jeremiah's imprisonment at and discharge from Johnson's Island is maintained at the Center for Historic and Military Archaeology at Heidelberg University. Today the university hosts a website for friends and descendants of the POWs.

In 1987, Jeremiah was named in the book 33rd Virginia Infantry, authored by Lowell Reidenbaugh and published by H..E. Howard, Inc. The volume confirms the date that Jeremiah deserted, but provides nothing more about his service.

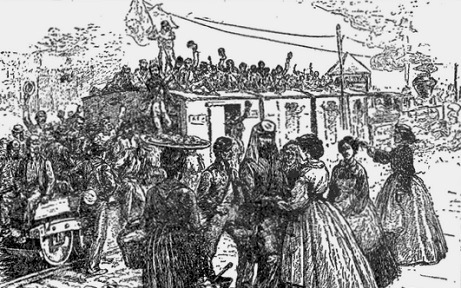

|

|

Confederate

POWs pledging allegiance to the USA. |

~ Service in the Union Army and a Wound in Florida's Largest Battle ~

Jeremiah's term with the 48th New York originally was to be three years. At the time of his enlistment, the regiment was in camp at Beaufort, SC, following a disastrous loss at Fort Wagner. Thus he quickly would have been transported from Albany to Beaufort, a distance of almost 1,000 miles.

"There tents were pitched in a wood about three miles from the landing, and the regiment was once more in camp," said Abraham John Palmer's 1885 book, The History of the Forty-Eighth Regiment New York State Volunteers. (See full-text via Google Books.) "Many of the wounded officers and men from Fort Wagner who had recovered now returned to the regiment, and one hundred and fifty recruits from the North were added. The addition of these two full companies, the recruits, and the return of the wounded men, greatly increased the strength of the regiment."

|

Olustee battlefield monument, three miles east of town |

Jeremiah thus joined a body of men which "was but the shattered remnant of its former self," Palmer wrote. The regiment was ordered to Fort Pulaski, GA for a time and then moved to Hilton Head. At Christmas, the 48th New York hosted the 47th New York for a holiday meal, and on New Year's Day, the favor was returned. The month of January 1864 was quiet for the regiment, but then on Feb. 4 sailed to Florida on the steamer Delaware, arriving in Jacksonville. Their first battle of the year was at Olustee on Feb. 20, when the 48th advanced inland toward Confederate troops led by Gen. Finnigan. Wrote Palmer, the rebels were posted:

... in ambush, under cover of a swamp and a heavy pine forest, one flank resting on the woods and the other on Ocean Pond. [General Truman] Seymour marched his wearied men straight into that ambush, and they were at close quarters with the enemy as soon as they became aware of his presence. It was a critical situation, and a precipitous, sharp, sanguinary, and diastrous battle immediately ensued.... The enemy had the best of us from the very start that day.... To say that the whole brigade did its duty nobly is but faint paise. Under a most terrible fire it stood its ground with an unsurpassed courage. The Forty-eighth was subjected that day to an ordeal -- than which hardly anything is more trying to soldiers -- that of holding their line under a terrible fire from the enemy after the exhaustion of their own ammunition. For two hours and a half they fought with a valor which was never surpassed in their history.

The fight at Olustee cost the 48th New York 227 men killed, wounded and taken prisoner. Today the battle is considered Florida's largest of the war.

During the ordeal, Jeremiah was shot in the left ankle. The wound apparently was not serious, and he remained with the regiment. He and the 48th New York retreated to Jacksonville and then in March traveled by steamer Maple Leaf to Palatka, FL. About that time, an administrative decision was made to merge the regiment from the Department of the South into the Army of the James.

Recalled Palmer, "It was about to leave the little army with which it had hitherto operated amid the swamps and the sea islands upon the Southern coast, and to be merged in the great armies of the James and the Potomac, and participate in battles in Virginia and North Carolina of world-wide renown." The men left Palatka in mid-April, leaving behind the graves of their dead "in the sands on Morris Island and the forests of Florida, not to speak of others scattered here and there along the coast," he wrote.

|

||

48th New York Infantry, Fort Pulaski |

||

|

||

|

~ A Shift Northward into the Bermuda Hundred Campaign ~

|

Gen. U.S. Grant at Cold Harbor |

The 48th New York traveled to Hilton Head on the steamer Ben-de-Ford and from there to Fortress Monroe, VA, with an unknown future ahead that would include important victories. At the time of the relocation, Gen. Ulysses S. Grant and the Union high command were planning an invasion of Richmond from the east. To do so, they had to penetrate through the town of Petersburg.

The troops on May 6 were ordered to a position at Bermuda Hundred, a spit of land sandwiched between the James River and the mouth of the Appomattox River. En route, as they marched, many of the New Yorkers gave back heavy equipment and baggage they had been carrying, only keeping the lighter bare essentials such as tents, blankets and clothing. Said Palmer, "fifty pounds on one's back soon gets heavy after a few miles of marching, and whenever we halted for a rest the men would examine their knapsacks and throw away whatever they could spare. Knapsacks that had been packed full at the start soon were well-nigh empty."

While at nearby Chester Heights, VA on May 7, also known as Chester Station, the 33rd New York was ordered to help destroy the Richmond and Petersburg Railroad line. It was all a part of a push toward capturing Petersburg. Confederates were waiting, however, under the command of famed General Pierre G.T. Beauregard, and a skirmish began. Palmer recalled that it was "a square stand-up fight." The 48th was the lone regiment to reach the rail line and tear apart long sections of it. In hand-to-hand combat, Jeremiah was wounded again, receiving a sabre cut of his right shoulder.

Nine days later, at Drewry's Bluff on May 16, the soldiers were roused from sleep and began to move at 3:30 a.m. in a heavy fog which caused great confusion. As the Confederates cut through Union lines, the lack of visibility prevented them from doing any more than turning the Union's right. "You did not know friend from foe," one observer noted. Back and forth volleys continued throughout the day. During 13 desperate hours, the 48th New York was in the center of the fight and performed admirably amid an otherwise Union loss.

And so the war dragged on, with no side gaining an advantage, and no end in sight for the weary Jeremiah and his mates.

|

Above: Kurz & Allison's depiction of the Battle of Cold Harbor. Below: rotted corpses gathered from the Cold Harbor field. Library of Congress. |

|

With Grant continuing to swing around the enemy, to gain more of a foothold in the press toward Richmond, more than a week of heavy action took place at Cold Harbor, from May 31 to June 12. The battle claimed a total of 19,000 casualties. Jeremiah and the 38th were instrumental in capturing rebel rifle pits in a wooded area and securing 600 prisoners. In the action, the regiment lost its battle flag, a very serious embarassment earning an official reproach.

The next days were filled with bloody back and forth charges. Wrote Palmer, for five days the 38th "was constantly in the rifle-pits, under a fire that never ceased by night or day -- first on the right, then on the left, then at the front; and everywhere it sustained its reputation for valor and efficiency. The ground between the lines of the contending armies was strewn with dead and dying soldiers of either side, but so incessant and so hot was the firing that it was certain death attempt to reach them."

Grant ordered one final assault against heavily fortified positions. It failed with an astonishing loss of life. Years later, Grant admitted in his memoirs that ""I have always regretted that the last assault at Cold Harbor was ever made.... No advantage whatever was gained to compensate for the heavy loss we sustained." Then on June 11, the 48th New York was ordered to stay put as the bulk of Union forces marched away from the Cold Harbor field. Many in the regiment felt they might be left there, sacrificed for the greater good of the army. But they survived the ordeal and finally were evacuated two days later. Wrote Palmer, "Nothing in the history of the war was finer than the holding of the lines at Cold Harbor during the change of base by Grant's army. It only could have been accomplished by veteran soldiers in the highest stages of discipline."

|

The wounded arriving at Fortress Monroe for transport to the post hospital in horse-drawn ambulances. Famous Leaders and Battle Scenes of the Civil War |

High praise indeed for Jeremiah and his New Yorkers. He somehow again was not harmed in this series of terrible, horrible battles, considered the "fiercest" of those during Grant's Overland Campaign against Lee. Harvard President Drew Gilpin Faust, in her bestseller This Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War, called Cold Harbor and the earlier Malvern Hill "profligate squandering of lives." Ironically, Jeremiah had fought in both battles, on both sides.

From Cold Harbor, Grant's plan was to capture Petersburg which if successfuly would leave Richmond unprotected. From June 30 to July 30, Jeremiah's regiment was part of an extended siege, with trenches dug by Union forces ringing east and south of town. On Aug. 11, at nearby Strawberry Plains, he suffered a serious wound to his right hand when his musket exploded, resulting in the amputation of his thumb and damage to the forefinger. After this third wound, he was sent to the U.S. Army General Hospital at Fortress Monroe, VA. He then was transferred to the U.S. Army General Hospital in Newark, New Jersey, remaining there until September 1864.

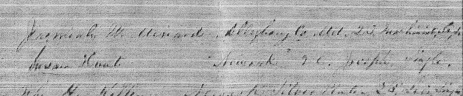

While convalescing in Newark, on Aug. 30, 1864, the 23-year-old Jeremiah did something that may have been spur-of-the-monent, given the transient nature of his existence. He married 26-year-old Susan Hunt (1837-1882), daughter of Joseph and Mary (Adams) Hunt. Susan was four years older than her husband and a native Northampton County, PA. How they met during such a short stay is lost to history. On their New Jersey marriage license, he gave his middle initial as "W." and his hometown as "Allegheny" County, MD.

From Newark, Jeremiah was sent to Fort Wood in New York, and rejoined his regiment in October 1864. He was transferred to North Carolina and was there when the war closed. He received an honorable discharge at New Bern on June 6, 1865.

His journey had covered more than four years as an eyewitness to the harshest military experience -- 13 battles, three wounds, grisly losses of uncountable friends on both sides, hundreds of miles of hard marches, arrest and imprisonment, and extended separation from loved ones.

|

Above: marriage record for Jeremiah and Susan, 1864. Below, his admission to the New Jersey Home for Disabled Soldiers. New Jersey State Archives |

|

~ Rapid Decline in Postwar Years ~

Now truly free, after more than four years of an extended, surreal combat experience, Jeremiah returned to his wife in Newark. He may not have been in a position to go back home tof Preston County, perhaps knowing that his reputation would mark him for ridicule, hatred or even violence. Brother-in-law John K. Martin, a Union veteran, living in Preston at the time, may have factored into the decision to remain in New Jersey.

How he would have dealt with any post-traumatic stress or memories of carnage can never be known. To earn a living, the former farmboy took up a career as a machinist.

In about 1869, suffering from his wartime wounds, Jeremiah was awarded a pension from the federal government as compensation, with $4 in checks arriving every month. He drew these payments for the rest of his life. Interestingly, the New York Times once reported that many former Confederates who had switched sides were receiving money from the federal government. In 1894, the Times reported that "It is a fact not generally known that a large number of ex-Confederate soldiers and sailors who deserted, or who, while prisoners of war, took the oath of allegiance to the United States, enlisted in the Union Army, and, receiving disabilities while in the line of duty as Federal soldiers, are now drawing pensions.... Several regiments were also enlisted from among the Confederate prisoners at Sandusky, Columbus, Camp Chase, Johnson's Island, Fort Delaware, and other military prisons."

When the federal census was taken in 1870, Jeremiah and Susan made their home in Newark, NJ. At the time, he was age 29 and Susan 33, and his occupation was as a saw mill worker.

|

|

|

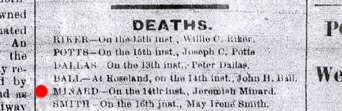

Only a brief mention of Jeremiah's death was published in the Newark Morning Register, July 18, 1881 |

Jeremiah's mental health declined precipitously, and he was diagnosed with epilepsy. On May 20, 1872, at the age of 32, he was admitted to the New Jersey Home for Disabled Soldiers. One surgeon working for the Home wrote that Jeremiah had "lost nearly the whole of the right hand since the war." He apparently was in and out of the Home during the 1870s, often treated as an outpatient. But he was taken to the Essex County Insane Asylum on May 19, 1879.

Right around that time, they adopted a daughter Nettie, born in 1878.

The 1880 census lists Jeremiah twice. The first shows him (spelled "Jireinyr") , Susan and their adopted two-year-old daughter Nettie residing in a home on the north side of East Kinney Street in Newark. Tragically, it states that the 39-year-old Jeremiah was an "engineer" who had "lost his right hand, became insane" and was "in Essex County insane retreat, is like a child."

Tragically, but perhaps blessedly, Jeremiah's miseries ended with his passing, at age 37, on July 16, 1881. The cause was ascribed to apoplexy following epilepsy. His tired remains were placed at eternal rest in Newark's Fairmount Cemetery, in the Civil War soldiers section. Research by cousin Eugene Podraza shows that the death was not recorded in Essex County, nor is there an estate file or last will and testament. The only notice of his passing was a one-line mention in the Newark Morning Register, on July 18, 1881.

|

| Entrance to Newark's Fairmont Cemetery |

[In 2014, an effort was made to examine Jeremiah's old hometown newspaper, the Preston County Journal, in the event it might have carried a notice of his death. The microfilm was found in the West Virginia Regional History Collection at West Virginia University, but it was mounted backward, and could not be fixed during the visit.]

Susan only outlived her husband by a year-and-a-half. She made her home at 45 Hermon, a short street of only six blocks, stretching between Chestnut and Thomas Streets, and intersecting with South Street, to the southeast of Lincoln Park.

At age 45, afflicted with peritonitis, Susan died on Dec. 5, 1882, after suffering for two weeks. She too was laid to rest in Fairmount Cemetery.

~ Adopted Daughter Nettie Minard ~

Adopted daughter Nettie Minard (1878- ? ) was born in about 1878 in Pennsylvania.

Living in Newark in her early years, she was only four years old when her adoptive mother died, rendering her an orphan.

Her fate seems lost to history. Was she taken in by her mother's family? Or an orphanage? Research is underway to determine the rest of her story.

~ For More Reading ~ |

33rd Virginia Infantry, by Lowell Reidenbaugh. For Cause and Comrades, by James M. McPherson. Four Years in the Stonewall Brigade, by John O. Casler. "Plain Living at Johnson's Island," The Century, March 1891, by H. Carpenter. Rebel Yell: The Violence, Passion, and Redemption of Stonewall Jackson, by S.C. Gwynne. The First Battle of Manassas: An End to Innocence, July 18-21, 1861, by John J. Hennessy. The History of the Forty-eighth Regiment New York State Volunteers, by Abraham John Palmer. The Stonewall Brigade, by James I. Robertson Jr. This Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War, by Drew Gilpin Faust. |

|

Copyright © 2008-2011, 2013, 2014, 2019-2020 Mark A. Miner |

|

Jeremiah Minard grave photograph by Eugene F. Podraza. Wheeling Intelligencer clip courtesy of Chronicling America. 1st Manassas railroad, camp discipline and field hospital sketches from Four Years in the Stonewall Brigade/Google Books. 2nd Manassas sketch from Famous Leaders and Battle Scenes of the Civil War. Johnson's Island sketches from "Plain Living at Johnson's Island," The Century, March 1891. Chris Marsicano of Delevan, WI has researched the Hunts, with the records shared by the Northampton County Historical and Genealogical Society in Easton, PA. |