|

Albert

Miner |

Albert Miner was born on Dec. 30, 1843 in Champion, near Warren, Trumbull County, OH, the fifth of 13 children of Joseph and Elizabeth (Forney) Miner. Sadly, while in the Union Army during the Civil War, he lost his life in the service of the nation.

During the war, on Sept. 7, 1861, Albert and his brother Samuel both joined the Army. Albert, according to neighbor Charles Diehl, was:

...but a stripling not to exceed 18 years of age when he enlisted and he lived with his father and mother up to time of his enlistment. He worked for them on their farm. He never was married and left neither widow nor child surviving him.

Albert and Samuel were assigned to the 19th Ohio Volunteer Infantry, Company C. Later, on New Year's Day 1862, Albert was transferred to Co. H of the regiment.

|

|

Horrific fighting at Chickamauga, where Albert was captured |

|

Chickamauga battlefield in peacetime |

During the Battle of Chickamauga, on Sept. 19, 1863, Albert went "missing in action," and was taken as a Confederate prisoner of war. Part of the Chickamauga battlefield, near Chattanooga, TN, is seen here in a rare old postcard photograph, taken in later peacetime, showing a deceptively peaceful site. Dated 1902, the postcard shows the Snodgrass house, which served as the Union Army headquarters of Maj. Gen. George H. Thomas, preserved at the battlefield park some 39 years after the horrific fighting.

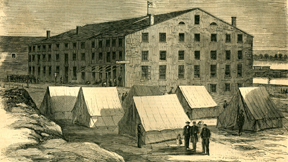

Albert was transported to Richmond, VA and held for three months in the notorious Libby Prison. Libby was a squalid, filthy and deadly facility, and considered one of the Confederacy's worst.

|

|

Libby Prison, Richmond |

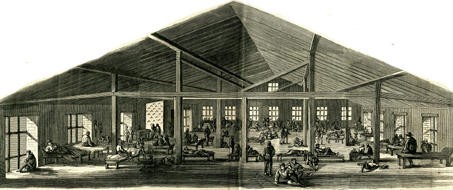

One Libby prisoner complained of having to sleep on bare floors, in front of open windows, with insufficient clothes or blankets. The men also were exposed to cold temperatures, dampness and germ-carrying insects from the nearby, slow-flowing river. Sanitation was non-existent -- prisoners relieved their bladders and bowels in the corners of their rooms.

Suffering from the "effects of Prison Life" at Libby, Albert was sent on Dec. 12, 1863 to Danville, VA, where he was admitted to the Danville Confederate General Hospital for further care. Sadly, Albert lingered for a little over two more months as his health declined further. Records say that his condition was "Variola," a virus better known today as smallpox, marked by inflamed eruptions in the skin.

Since smallpox was so deadly and contagious, a separate hospital facility was built in Danville exclusively for the POW victims. He most likely was moved there in mid-February 1864, and died there on Feb. 20, 1864, or more likely on March 17, 1864, one of five POWs to die there that day. Albert's remains were buried in what is now an unknown location.

|

|

Living conditions in Libby, where men like Albert spent days filled with despair |

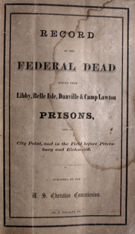

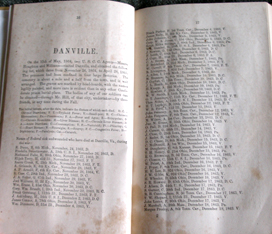

The year the war ended, the U.S. Christian Commission visited many of the Civil War prisons in Virginia, gathering the names and burial sites of the dead. Its findings were published in the book, Record of the Federal Dead Buried From Libby, Belle Isle, Danville and Camp Lawton Prisons. Albert's name is published on page 24, in the chapter on Danville. In the preface to the Danville chapter, the authors wrote:

The prisoners had been confined in four large factories. The cemetery is about a mile and a half from town, and is well arranged. The graves are marked by head-boards, with the names legibly painted, and more care is evident thanin any other Confederate prison burial-place. The bodies of any of our soldiers can be obtained--through Mr. Hill, of that city, undertaker--by their friends, at any time during the Fall.

|

|

Albert is named in a rare Civil War era book listing the dead in Confederate prisons in southern Virginia |

T. Lawrence McFall Jr., a board member of the Danville Historical Society, has written a book documenting the smallpox hospital in some detail. Entitled Danville in the Civil War, it's part of the Virginia Civil War Battles and Leaders Series. In a 2004 letter, McFall wrote that he believes Albert originally was buried at the hospital's cemetery:

In 1955, no headstones were located when their makeshift cemetery, more than one mile distant from the National Cemetery, was removed to Danville's Oakhill Colored Cemetery and placed in a common grave at that time. It was decided [at that time] that the remains were those of Negro residents of the nearby Alm's House (Danville poor house) late in the nineteenth century. Only years later was it determined that these remains were those of Union smallpox patients.

|

Libby Prison, Richmond |

Thus it's believed that Albert's final resting place is Oakhill Cemetery in Danville.

Many years after his tragic death, Albert's name was mentioned in a March 1881 article in the Western Reserve Chronicle newspaper in his hometown. The lengthy story described the first encampment of the Grand Army of the Republic, a national veterans' organization. In the article, Albert was among 31 honored members of the Company who comprised their "dead comrades." Of those soldiers in the regiment who had made the ultimate sacrifice, the article said:

I see another table around which are seated the phantom forms of many brave ones who marched gaily out with us, but who came not back,... [They] lie where they fell, by mountain side, by gentle streams, in quiet valley, or gathered into the great cities of the dead at the South. We whisper their names; we think how they looked as they left camp for their last trick of picket duty, or as they took their places in line for the last battle. They were brave boys; none braver ever faced the cannon's mouth. None more cheerfully endured the weary march or the lonly [sic] picket watch.

Albert's name is permanently enshrined on the "Honor Roll" page on our website honoring wartime military casualties in our family.

He is mentioned in a lavishly illustrated, 2011 book about one of his cousins who also was a Civil War veteran -- entitled Well At This Time: the Civil War Diaries and Army Convalescence Saga of Farmboy Ephraim Miner. The book, authored by the founder of this website, is seen here [More]

| Copyright © 2003-2004, 2006, 2008, 2011, 2019 Mark A. Miner |

|

Libby Prison sketch by Capt. Harry E. Wrigley, Topographical Engineers, and originally published in Harper's Weekly. |