|

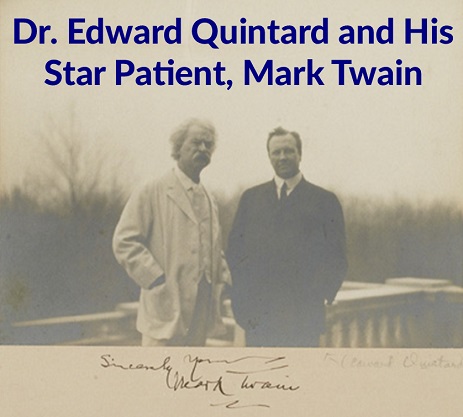

| Edward and Twain - courtesy University of Virginia Library |

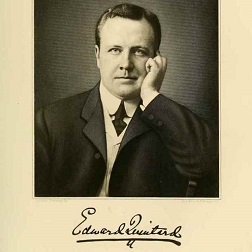

Dr. Edward Skiddy Quintard -- husband of our cousin Estella Hayden of Columbus, OH -- was the personal physician to many celebrity patients during his career. By far the most famous was world-renowned bestselling author Samuel Clemens, better known by his pen name of "Mark Twain."

- courtesy College of Physicians and Surgeons

The origin of their friendship is not yet known but may have taken shape in about 1904. In June of that year, during a stay in Florence, Italy, Twain's beloved wife Olivia died. Three months later their daughter Clara, suffering from over-exertion and depression, is known to have been admitted to Edward's sanitarium in Norfolk, CT for what author Ron Chernow called an "extreme 'rest cure'." In this environment, Edward allowed her no guests, no letters and no other reading material. During that treatment, Chernow writes, Clara "slept normally for the first time in a year. Able to sing and play the piano again, she projected a concert tour that winter; the doctors even granted her a July visit from her father and sister."

Twain was delighted with this care for his daughter. He and the Quintards are known to have exchanged letters in that same year 1904, with Edward's notes preserved today by the Mark Twain Project at the University of California's Bancroft Library.

When Twain's other daughter Clara suffered an attack of appendicitis in May 1905, Edward assisted New York physician Dr. Frank Hartley in the surgery. Reported the Elmira (NY) Star-Gazette, Miss Clemens is a handsome young woman, well known in Elmira, where the family has relatives and where Mrs. Clemens lived. Miss Clara Clemens has inherited her father's wit, and, besides, is an accomplished vocalist."

Edward prescribed a mustard bath for a Twain illness early in the relationship. Then in the heat of August 1905, Twain became stricken with gout at his summer cottage at Edgewood, shortly after attending the funeral of his nephew Samuel Moffett, who had drowned at the Jersey Shore. Edward traveled to attend his star patient in person. With Twain nauseous and unsteady on his feet, Edward advised him to stay close to home until the weather cooled.

|

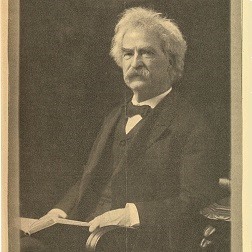

Samuel Clemens - "Mark Twain" |

When Twain celebrated his 70th birthday in early December 1905, Edward attended a dinner in the author's honor at the famed Delmonico's Restaurant in Lower Manhattan, and was pictured in a special souvenir edition of Harper's Weekly magazine. The dinner was organized by Twain's publisher, Col. George Harvey of Harper & Bros., and editor of the North American Review. Attended by some 170 friends and fellow authors, the dinner featured "a great many toasts and tributes and poems, and telegrams of congratulations from everybody from President Theodore Roosevelt down," remembered Life Magazine 39 years later, in 1944. "As usual, Mark Twain made the best speech of the evening."

Among the notable guests at Twain's dinner were famed naturalist John Burroughs; steel industrialist and philanthropist Andrew and Mrs. Carnegie; Willa Cather, Pulitzer Prize winning author of O Pioneers! and My Antonia; Native American physician and author Charles A. Eastman; Little Lord Fauntleroy author Frances Hodgson Burnett; Atlantic Monthly editor and American Academy of Arts and Letters president William Dean Howells; George Washington biographer Rupert Hughes; Perils of Pauline author Howard McGrath; literary executor of Elizabeth Bacon Custer, General Custer's widow, Marguerite Merington; Twain biographer and Pulitzer Prize committee member Albert Bigelow Paine; magazine writer and future best-selling author of books on etiquette and good manners; and Standard Oil's most senior and powerful board director, Henry H. Rogers, who helped reorganize Twain's extensively troubled financial condition.

|

|

| Edward, far left, pictured in Harper's Weekly at Twain's 70th birthday dinner at Delmonico's in New York. He is seated with, L-R: Louise Morgan Sill, Caroline Ticknor, Dr. C.C. Rose, Olivia Howard Dunbar, Weymer Jay Mills, Bert Leston Taylor and Gabrielle Jackson |

|

Edward and Twain named in Harper's |

Edward was seated at the Twain celebration with poet and literary translator Louise Morgan Sill; writer and biographer Caroline Ticknor; digestive medicine expert Dr. C.C. Rice; short story writer Oliva Howard Dunbar; fiction book author Weymer Jay Mills; Chicago Tribune journalist and humorist Berg Leston Taylor; and author Gabrielle Jackson.

The Quintards were eager to support Twain's daughter Clara, who was an aspiring vocalist, by hosting a musical party at their home at 145 West 58th Street in March 1908. At that small private affair, Clara performed, accompanied by Will Wark on piano and Lillian Littlehales on the cello.

But Edward became tangled in several Twain family controversies over the years. During that period, the widowed Twain lived in Redding, CT in a newly built mansion known as "Stormfield." He shared that home with his unmarried daughters Jean and Clara, and with Twain’s longtime housekeeper/business manager, Isabel Lyon, and several servants. Sadly, daughter Jean was afflicted with epilepsy, resulting in convulsions, erratic behavior and mood swings. In that era, epilepsy carried a dark stigma kept hidden to the public. In her book Mark Twain’s Other Woman, Laura Skandera Trombley writes that Edward "regarded Jean as a physical threat and dangerous to those around her; he warned Isabel [Lyon] 'never to let Jean get between her and the door, and never to close the door'." He continued to be consulted when Jean was stricken with multiple seizures over short periods of time.

Twain's daughter Clara is said to have borrowed funds "heavily" from the Quintards, despite her father's own wealth, although the details are not yet known.

In the summer of 1908, Twain suffered severe chest pain. Edward again traveled from New York to make a personal examination. He is mentioned for this episode in Albert Bigelow Paine's biography, Mark Twain: A Biography, (initially published in installments in Harper's Magazine). Wrote Paine, Edward "did not hesitate to say that the trouble proceeded chiefly from the heart, and counseled diminished smoking, with less active exercise, advising particularly against Clemens's lifetime habit of lightly skipping up and down stairs."

|

| Modern Twain biographies naming Edward -- L-R: Mark Twain: Man in White: The Grand Adventure of His Final Years, by Michael Shelden (2010) -- Mark Twain's Other Woman: The Hidden Story of His Final Years, by Laura Skandera Trombley (22010) -- and Mark Twain, by Ron Chernow (2025) |

In early 1909, Twain's longtime housekeeper Isabel Lyon, who for years had been a deeply trusted confidant, was dismissed after allegations of financial embezzlement and sharply divided rifts with Twain's daughters. Edward himself suspected impropriety and expressed his opinions to Twain’s daughter Clara. The stress throughout the household was dangerously high. Just a few months later, Twain was stricken by a sharp pain in the center of his chest. Edward diagnosed it in his own words as "tobacco heart," and told him to cut back on his daily consumption of 40 cigars. He repeatedly told Twain that continued smoking would kill him.

In response, Twain wanted to know how many years more he had to live. "I was in hopes that Quintard would tell me that I was likely to drop dead any minute; but he didn’t," he said, as quoted in Michael Shelden’s book Mark Twain: Man in White. "He didn’t give any schedule."

|

| Above: Twain's daughters Clara (left, with husband Ossip), and Jean, all three of whom Edward treated. Below: Clara's wedding, which Edward attended. L-R: Twain, Jervis Langdon Jr., Clara and Ossip, Jean, and Rev. Joseph Twichell. Library of Congress |

|

|

Book naming Edward |

Twain was entering the final winter of his life. Edward recommended that he not spend those cold months in Connecticut, fearing that an attack of bronchitis or influenza might aggravate his heart. The doctor suggested instead that he go to Bermuda, and armed him with syringes and opiates and instructions on how to use them. Twain sailed there in late November 1909 and after a month of relaxation returned home just before Christmas.

Compounding the heartache, on Christmas Eve morning, Twain was awakened to learn that his beloved daughter Jean had been found dead in the bathtub of their home, apparently from heart failure. He viewed her body in the bathroom, covered by a sheet, and felt as though he was a soldier who had been mortally shot.

Edward sent Twain a card later in the day, saying:

I love you beyond all words, beyond all measure of words, you who have been such splendid and noble and exalted thoughts and for us all.... I sent Miss Gordon because I know what a tremendous help she can be to you and she is to let me hear at once. I cannot tell Estella, she has been so very ill. I dare not speak of anything so tragic and sad lest the shock be more than she could stand. Her love for you is deeper and truer than you ever can know, as for it, it is only her condition that prevents my coming to you at once. God knows my heat and sentiments and love are with you every moment.

|

|

Edward's Christmas Eve condolence to Twain, 1909 |

It was the end of Twain. A week later, on April 21, 1910, as Twain lay dying, Edward was at his bedside. During that day, the patient quietly slipping away. In the biography, Paine elegantly captured the scene:

During the afternoon, while Clara stood by him, he sank into a doze, and from it passed into a deeper slumber and did not heed us any more. Through that peaceful spring afternoon the lifewave ebbed lower and lower. It was about half-past six, and the sun lay just on the horizon, when Dr. Quintard noticed that the breathing, which had gradually become more subdued, broke a little. There was no suggestion of any struggle. The noble head turned a little to one side, there was a fluttering sigh, and the breath that had been unceasing for seventy-four tumultuous years had stopped forever.

Following Twain's death, Edward was one of 5,000 who "crowded Carnegie Hall ... to honor the memory," said the Publisher's Weekly. "While almost every one of prominent in the literary life and activity of the Eastern half of the country, was present, there were many others besides, representing business, finance, and all the professions." Among the best-known personalities in the audience for the memorial was J.P. Morgan and Mrs. Andrew Carnegie.

|

Twain's "Stormfield" home and bedroom in Redding, CT, where he died with Edward at his side |

|

Copyright © 2009-2010, 2013, 2016, 2025-2026 Mark A. Miner |

|

Dr. Quintard's portrait is from History of Medicine in New York, Vol. V, by James J. Walsh (1919). Twain portrait and bedroom images courtesy of the Library of Congress - American Memory Project. Quintard/Twain photo courtesy of the University of Virginia Library. Quintard letter courtesy of the Mark Twain Project, University of California Bancroft Library. Kensico mausoleum and grave photographs courtesy of Linda Burton Kochanov. |