|

Chills,

Fever, Friends |

|

Also

see the "Great Oklahoma Land

Rush of 1889" - |

|

|

Laura Barnum |

[Note -- this memoir by Laura (Brown) Barnum, about the early pioneer settlement era of Oklahoma, was originally printed by the Kingfisher Free Press on April 17, 1939, and was reprinted in the book, Echoes of Eighty-Nine, by the Kingfisher Study Club. It is republished here with permission of the family.]

In the spring of 1889, at the opening of Oklahoma proper on April 22, J. R. Brown and family of Medicine Lodge, Kans., came to Oklahoma and made the race for claims from the line a mile west of Kingfisher. My sister, Nellie Brown Jones, in her story of ‘89, told how she and I made the race, driving a mule hitched to a one-horse buggy and, of staking her claim just south of where the Kingfisher cemetery now is.

Father failed to get a claim at once, but later bought a man’s right to one in Excelsior township. My brother Frank also failed, but got one late at the mouth of Kingfisher creek.

For the first two or three weeks we all camped with my sister Nell on her claim in a small 10 x 14 tent. About this time, George Johnson, who lived in the Cheyenne country, just across Kingfisher creek to the northwest of where the cemetery now is, made father on offer for us to move over to his ranch and milk cows and run a dairy for Kingfisher, giving him a certain percent of the profits. Several of the homesteaders, who had brought a few cows with them into the country, were selling milk, but there was not enough milk to supply the demand. Mr. Johnson had an Indian wife, but she died soon after the opening of Oklahoma. He lived on Indian allotment land and had large herds of cattle.

He had two cabins on his ranch and he offered us one to live in. So father accepted his offer, and we moved over there, and began driving in cows off the range to try to break them to milk.

|

|

Laura's memoir in the Kingfisher Free Press |

Father hired an experienced cowboy to help. He would rope them, tie them down by head and heal. We had many narrow escapes when they sometimes broke all ropes. But we stayed with the job and finally broke 40 cows so we could milk them.

My father, brother Frank, sister Nell and I did all the milking, 10 cows each twice daily. We milked at 2 o’clock in the morning and 2 in the afternoon, as the milk had to be delivered before 6 o’clock in the morning and 6 in the evening.

Mother strained the milk as fast as we milked it and Frank delivered it. He had two big cans made to put on a platform in the front of a one-horse buggy, high enough so a quart measure could be placed under the faucet which was placed at the bottom of the can. He would drive up to a house, ring a bell and the housewife or children would come out with a bucket or pitcher to get what milk they wanted.

We began running the dairy the latter part of May, 1889 and continued at it until the latter part of October, 1889. Then father had to go to his claim in Excelsior township, so we quit the dairy business. That was Kingfisher’s first dairy and was known as the Johnson and Brown Dairy.

Mr. Johnson continued to run the dairy for some time after that -- I don’t remember just how long. My brother Frank stayed with him and delivered the milk for him for quite a while. Then he also had to quit and go to his claim.

|

|

Famed Pioneer Woman Statue in Oklahoma |

I stayed part of the time with my sister on her claim in the dugout and part of the time with my parents on their claim in the woods in Excelsior Township.

The man from whom father had bought the relinquishment had built a log cabin on the claim, about 14 x 16 feet. It had a dirt roof and the ground for a floor. A door and one small half window in each end. It wasn’t a mansion, but it was a shelter, and we moved in, looking forward to the day when we could have the new cabin father was planning to build.

The cabin was near a small creek in the heavy timber, and the trees were in their beautiful autumn color of red, green, and gold. After our hard summer’s work of running the dairy, it was just one grand vacation picnic to my younger sisters and I, and mother enjoyed it, I think, as much as we did. Oh, those beautiful bright October days. How the memories of them come thronging back. How we wandered through the woods, the quail and rabbits fleeing before us, and the squirrels watching us from the tree-tops as we hunted the red and black haw berries, the persimmons and nuts.

But it wasn’t all play. There was plenty of work to do, but we made play out of work. Father at once began clearing land, cutting down the trees where he wanted his farm land, saving the best logs for the new cabin we planned to build, then cutting and sawing the rest into wood and posts. I have pulled one end of a cross-cut saw many a time, helping father saw off the post cuts. Then we would pile the brush into big piles. Then in the evening, what beautiful big bonfires we would have!

The first thing father did, though was to plow and burn out fire guards around the cabin to make it safe from a forest fire, which came later in the fall, fanned by a high wind from the north. The grass was so rank that year that the flames reached to the dry leaves on the small blackjack and went to the tops of them. When we saw it coming, we tied our cows to trees near the cabin, then went into the cabin and closed the door and windows to keep from suffocating from the heat and smoke. But the fire guards kept it from reaching the cabin and we were safe.

Nearly all our neighbors moved to their claims that fall, and we would know a new neighbor moved in by the crowing of their roosters or barking of their dogs. And it didn’t take us long to get acquainted--and such good neighbors as they all proved to be. I think I have never lived any place that had a better class of people in it than those who came into the Excelsior neighborhood. I must praise them a little, for they were an intelligent lot of people, and such good, kind friends and neighbors in sickness and in health, in joy and sorrow.

|

|

|

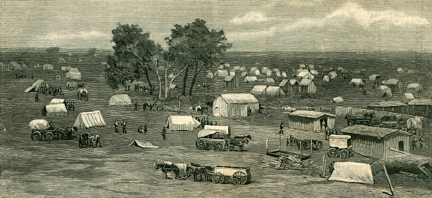

The founding of Oklahoma City -- the new state's capitol |

All were very busy for many weeks and months, building their homes and getting settled. Were times hard? Oh! yes! Surely they were. But I think we had a little better chance at making a living in the timber than those who lived on the prairie did. For we could cut a load of wood and haul it to Kingfisher to buy our groceries. One could buy as much than for $2 as one can now for $5. We didn’t get much of price for the wood, but it kept us from going hungry. Then lots of people gathered up the bones of cattle that had died in years past and hauled them to Kingfisher and got from $1.25 to $2 a load according to the size of the load. I remember we gathered a load and father got $2 for it. He gave it to we girls and we got us some new calico dresses -- print, we call it now -- and I have never forgotten that dress. I know just the pattern of it yet although 50 years have passed since then. And I remember the miles we tramped in getting the bones. They were pretty well picked up before father let us try to get a load -- and I think we got the last bone in the Excelsior community.

It was while out hunting the bones that I saw my first and only wild deer in Oklahoma. Mother was driving and we were out looking for bones. Suddenly she called: “Look quick, girls, at the left.” And there went two deer racing away through the woods. There were still a few left in the woods -- and some reported to have killed wild turkeys and wild hogs, but we never saw any.

I have gone with father to drive one team and wagon and he another to haul many a load of wood to Kingfisher, 18 miles. We would have to ford the river for there were no bridges. We had to double across the river--put both teams on one load, take it across, then ride the horses and one of the horses and lead the others, and go back for the other load; then on to Kingfisher, where father would sell one load and I would take the other load over to my sister’s claim, where she lived in a dugout. Maybe we would stay all night there and go home the next day.

Toward spring, when it began to rain more, we had a hard time keeping the dirt roof on our cabin. It would wash off and we would have to put more dirt on it. Then one night an awful rain came, and what didn’t wash off on the outside came through on the inside. I remember seeing mother sitting there, holding an old umbrella over her and the younger girls to keep the muddy water off, while father and I just put on some old coats and took the muddy bath.

After that we moved into the old tent and father rebuilt the cabin and built it up to a story and a half, making some sleeping rooms upstairs. He split some clapboard shingles from oak logs for a roof. He built a lean-to kitchen and put floors in all of it, plastered up the cracks with lime and sand. And we surely were proud of that new cabin home.

It was while living in the tent that we heard a panther crying in the woods. Father had gone to Kingfisher and mother, the younger girls and I were alone. Just after we had retired we heard it cry--first on one side of the tent, then on the other. Mother lighted the lamp, as we had heard they wouldn’t go very near to a light. It didn’t seem to come any closer, but nearly all night we would hear its cry. It seemed to me there must have been several of them, but they didn’t try to get into the tent. We kept the lamp lighted all night and kept watch. When morning came it had vanished into the woods.

Did we eat beans and salt pork and corn bread? Sure we did, and that wasn’t all. Wild game was plentiful -- quail, rabbit, squirrel, opossum -- and on the prairie. wild prairie chickens or sage hens, as some called them. We also had home-made hominy. and as soon as we got some ground in cultivation we added sweet potatoes, sorghum, pie melon and pumpkin butter, all seasoned with sorghum and spice. And it was all good (except the opossum: I didn’t like that). And we kept well and strong until the ague, malaria, chills and fever struck us.

For the first few years after the opening of the country we had that to contend with.Some thought the breaking up and rotting of the sod caused it. Then we had to drink lots of creek water and had been through lots of exposure. Anyway, what ever the cause, we had the chills: and they were the regular old shaking kind. We would shake until our teeth chattered and we thought we would freeze to death. But after a while we would stop chilling and begin to get warm: then get hot and still hotter. And then we were sure we were going to burn up with fever. But that would go down. The next day we would be up dragging around. But the next day would be chill day again -- every other day -- until we felt sometimes as though we couldn’t live through another one, as every chill made us feel weaker.

But the country doctors went from house to house and measured out the calomel and quinine, and most of us lived through it in spite of the chills and fever. The calomel and quinine, the remedy, was about as bad as the disease.I’ve wondered which killed the most the chills or the calomel. But the chills didn’t last all the time, mostly in the fall of the year. After a while we got used to the change in climate and living conditions, and chill days were a thing of the past and life took on a brighter hue.

What did we do for amusement? Well, after the people got there, homes where built, and everyone was settled, we first had what we called “get acquainted meetings,” Mr. Cater had the largest house, as he had built a new three-room frame house with a full basement, and they had an organ. Several others also had organs, but the Caters had the largest house and we had most of our meetings there. But sometimes we met at other homes.

Someone would go on horseback to each home and let everybody know when the meeting was to be held and where. Then when the time came, everyone would go -- young and old. There were many good singers among us and all who could sing did until we got tired. Then the older folks would visit, and the young folk would play games in the moonlight.

When warm weather came, we just had to have a Sunday School. There was no place to have it except out in the shade under the trees. So the Excelsior Sunday School was organized in Patrick’s grove. Some seats were made and we had it there until late in the fall when the weather began to get cold. Mr. Clump had started to build a new house, but had decided not to finish it until spring. He told us we could have Sunday School there if we could fix it up to be warm. So the place was enclosed and a stove was put up. Some benches were made to set on and we had Sunday School there until the new log school-house, which had been started, was built. The schoolhouse was named Excelsior, and the name still stands, although the old log school was replaced may years ago by a frame building.

Each family furnished some hewn logs for the walls of the school-house. Some big logs also were hauled to the saw mill which was running on the Van Kirk place, to be sawed into lumber to use in the construction. Split clapboard shingles from oak logs were used in the roof and to finish the building. The parents had to make seats for their own children, which they did, out of native sawed lumber. And they also made a desk for the teacher. Some pine boards, painted black, were used for a blackboard.

Then we were all ready for school, a three-month term, taught by Tom Finley, a young man in the neighborhood. It was a large school, something like 35 or 40 pupils, eight of we older girls, between the ages of 16 and 17 years, and on down to the small children. All of those children had been turned loose in the woods for two years, and now our parents had rounded us up and put us back in school. Poor Tom -- I pity him yet -- for it was awfully hard to obey school rules again. Oh, yes, some of them were model students; some of them were not. But he taught the school all right, was a good teacher and a fine young man.

We now had a place in which to have Sunday School, literary, spelling school, and the old soldiers had a G. A. R. post, which held its meetings there, as well as programs and bean soup, crackers and coffee--and those old soldiers surely know how to make bean soup.

Then we had an orchestra -- ”Prof. Farr’s orchestra,” we called it. Prof. Farr was a violinist and he played the violin, his wife the bass viol, her brother, Leisure Barnum, the cornet, Alva Barnum the trombone, and sometimes they used drums.

This orchestra furnished music for the literaries, picnics and old soldiers’ reunions at Dover, which would last a week -- a program every day and a barbecued beef at noon every day. They also played for dances all over the country.

Then we had old settler’s picnics in Garrett’s grove in the Banner neighborhood, and Sunday School picnics. I remember Excelsior Sunday School went to Twin Lakes in Logan County to a big union picnic. We all met at the schoolhouse and went in one long procession, one wagon right after the other. One man on horseback, with a blue and white sash around him, acted as marshal of the day. He led the procession. Then followed a load of children and young folks, carrying the Sunday School banner, with the name of the school on it, the girls all dressed in white, and the horses and wagon all decorated with flags and bunting. When we got to the picnic grounds, we marched to the platform singing some marching song, I forget what it was. Eight or 10 Sunday Schools were there that day. A big basket dinner was served and each school had a part in the program

Denominational creeds were forgotten in those days. Most of the Sunday Schools were union schools and we all met in one grand union.

Automobiles were unknown in those days and it was too far to go there for amusement. So each district provided its own amusement, then visited back and forth with adjoining districts. And there were more places to which to go then than there are now in the country, and I think we had better times.

Yes, I am an ‘89er and proud of it. I am glad I was brought here to hear the first gun fired that opened the first land for settlement and that I go to make the race. It was a wonderful experience I have lived here in Oklahoma all those 50 years except one year which I spent in California, and I have seen the development of this wonderful state. The building of its beautiful cities and farm homes, its industries, oil fields, mines, mills and its wonderful network of highways.It has been a pleasure to me to watch and read about all of it, and my only regret is that I can’t live those early years over again. But that cannot be, for we travel this life’s highway but once. The only backward road is down “Memory Lane,” and the call for these old ‘89er stories has taken many an ‘89er down that well traveled road. But like the old soldiers, who nearly all have gone on their last long march, a few years more and the last of the ‘89ers family will have made the last run, crossed the last line to file claims in that land “Where We’ll Never Grow Old.

| Originally published by the Kingfisher Free Press on April 17, 1939, and reprinted in Echoes of Eighty-Nine, by the Kingfisher Study Club. Text republished in 2001 by Mark A. Miner with permission of the family. Oklahoma City founding sketch republished from Harper's Weekly, May 18, 1889. |

|

Copyright © 2001, 2015 Mark A. Miner |