|

Pera

(Minerd) Jewell |

Pera (Minerd) Jewell was born on Feb.

16, 1844

near New Rumley, Harrison County, OH, the daughter of Samuel

and Susanna (Hueston) Minerd. She and her husband are considered pioneers of

Wood County, OH.

Pera Jewell

As a young girl, Pera moved with her parents to Tontogany, a small farming community in Wood County.

Pera’s deep concern for her mentally ill brother Alpheus Minerd would lead her to extensive heartache and her husband to be the target of a grand jury investigation.

On Sept. 7, 1862, Pera married longtime friend and neighbor William Lacon Jewell (1841-1909), the son of John and Nancy (McCullough) Jewell, natives of Greene County, PA. William was born in Butler County, PA, and came to Wood County as a child.

Their wedding ceremony was performed in the home of Pera’s parents by Edwin Fuller, a justice of the peace and future local judge. The ceremony was clouded with controversy and, recalled Fuller:

On that day, Alpheus Minerd [hid] himself in the chamber above where the marriage ceremony was performed. The father and the family tried to get him to come down to the marriage … They failed to bring him down. The father then said that the boy was deranged and they could do nothing with him.

William and Pera together were the parents of eight children -- George Levi Jewell, William Samuel Jewell, Myra Josephine Caldwell, Edwin Jay Jewell, Lillian Farmer, Lena Leota Jewell, Jacob Arthur Jewell and David George Jewell. They also raised a motherless infant nephew to manhood, John William Shepard Jewell.

The Jewells were farmers, and also worked at the nearby Wood County Infirmary. Said the Bowling Green Daily Sentinel Tribune, "For 29 years [William] farmed the land adjoining the county infirmary which he still owned at the time of his death." William is said to have been an administrator at the home, and Pera a cook, according to the 1996 book, The History/Genealogy of John and Nancy McCullough Jewell: Their Ancestors and Descendants.

Sadly, son Jacob Arthur died the day he was born, on Jan. 8, 1871, and daughter Lena Leota passed away at the age of 22 on Sept. 10, 1894.

|

|

Wood County Infirmary |

Horror rocked the family when Pera's sister Sarah Jane Shepard died in childbirth in 1877 after delivering her seventh baby. The Jewells brought the infant boy into their home -- John William -- and raised him to manhood, giving him their name "Jewell."

Later in life, the Jewells resided in Bowling Green, Wood County. They were members of the local Baptist Church, and William was known as "an earnest Christian man" who had "many friends."

For about two months in 1866, and again for about four months in 1883, Pera suffered from mental illness and was institutionalized in what was then called an "asylum." Her husband once wrote that "Her insanity resulted from ulcerations of the womb each time," which may mean she suffered post-partum following births and/or miscarriages. As her illnesses corresponded with periods of years in which she had no children, this may suggest a cause.

By 1890, Pera's psyche had improved significantly. That year, her father Samuel observed that "She is sane now..." The Jewell History/Genealogy states that she once had a leg amputated at the knee.

|

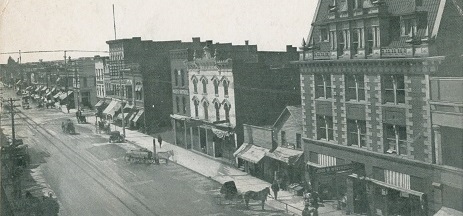

| Main Street, Bowling Green, circa 1906 |

~ Looking Out for Pera's Brother Alpheus ~

Through painful experience, the Jewells knew that Alpheus' mind and work habits were beginning to further slip after the Civil War. William reported that in October 1865, Alpheus "began to work for me. He worked for me four days, then went home; returned after two weeks, worked for me two days, then went home again."

Alpheus later returned to the Jewell home and agreed to work for his brother in law. But the arrangement did not work, Jewell said:

He worked for me again from April 1866 to about the middle of June 1866. Then I discharged him for abusing my horses. He again worked for me from Oct. 1, 1866 to the middle or last of Nov. 1866. In Oct. 1866, he disobeyed my orders in regard to work, got angry, came at me with a pitch-fork, and I seized & threw him and choked him unto submission, I never had any trouble with him afterward. The last of Nov. 1866, he went home, and never again worked for me.

Pera commented that he "was destructive and seemed to desire to kill & destroy. He killed my chickens & was cruel to the horses. He had a horse of his own but he was kind to that."

William also said that while working,

Alpheus was "cheerful and all right" but that in the evenings and on

Sundays, he was "silent, non-communicative, uneasy, restless, continually on

the move."

The Jewells with grandbaby Florence

In late 1868, Alpheus left home again, and wondered up into Minnesota. He did not return until March 1869 (or 1870). During his absence, he did not write to or contact his family in any way. After returning from Minnesota, he "was a great deal worse than when he went away, grew continually worse, and finally violent and dangerous," William recalled. "He seemed to have a grudge against his father. Pere said that "he got dangerous & threatened to kill my father."

Standing the abuse no longer, the family sought court protection. Alpheus was declared insane by the Wood County Orphans Court in a decision handed down in 1871. He was sent to an insane asylum in Newburg (Cleveland), OH. Later he was admitted to the Columbus Hospital for the Insane and to a mental health facility in Toledo, OH, remaining institutionalized for a total of 17-plus years.

On Oct. 19, 1881, the Orphans Court appointed William Jewell as his legal guardian.

Alpheus was released at the end of 1888, and returned to Bowling Green, where he moved back in with the Jewells. In December 1900, Alpheus slipped away and went to Green Spring, OH. William spent two days at Green Spring where he found Alpheus, bought him several meals and apparently brought him home.

~ Controversy Over a Civil War Pension ~

In February 1882, having spent much money on the care and feeding of Alpheus, William filed a claim to receive a federal pension for Alpheus' disabilities suffered as a POW. It took more than 8 years for the government to reach a conclusion.

William claimed to have had extraordinary expenses of $43.20 when Alpheus "ran away and [I] had to go after him." The costs included railroad fare and hotel bill for a trip to Green Spring, OH, where he found Alpheus, treated him to dinner and apparently brought him back to his old home.

|

| Depot of the Cincinnati, Hamilton & Dayton (CH&D) Railroad in Tontogany |

The Jewells used the pension money to buy Alpheus an overcoat, suit of clothes and an "every day suit" as well as tobacco, mittens and suspenders. They also collected $102 from the pension funds for 34 weeks of board and washing.

At around the same time, the U.S. Attorney for the Northern District of Ohio investigated charges that William, his father in law and brothers in law had conspired criminally to defraud the government by lying that Alpheus had been normal before the war. A grand jury was convened in December 1889, and, fortunately for the family, apparently decided there was no grounds for a trial. Wrote Assistant District Attorney E.S. Cook, "The testimony before the grand jury certainly developed the fact that this man was sound and healthy, though with mental peculiarities, prior to his enlistment."

The government sent a printed warning to the Jewells at some point in time. It stated that they risked a fine of $2,000 and/or jail sentence of "hard labor for a term not exceeding five years" if they would embezzle a ward's federal pension or "fraudulently convert the same to his own use."

The government rejected William's pension

claim in March 1890. The Jewells were furious, and asked for reconsideration.

They hired Washington DC plaintiffs' lawyer George E. Lemon, nationally known

as a Civil War pension expert. (Lemon served as pension lawyer for many of our

Minerd-Miner-Minor cousins.)

Goveernment warning sent to the Jewells

The Jewells then procured favorable eyewitness testimonies from many of Alpheus' childhood friends, longtime neighbors and members of his Civil War regiment. These witnesses included Francis Franklin, Jacob C. Jeffers, Mary Jane Jeffers, Louisa Jeffers, John Soash, Hiram Cunning, Nancy McMann, Edward M. Foster, Ephraim Wires, Peter H. Van Valkenberg, James Jeffers, Greenberry Burditt, Wenmon Wade, David Murdock, William H. Shepard, Sarah Jane Patterson, Elizabeth Treadwell, Luis Godfred, William Crom, Samuel W. Whitmore, Alburtis Russell, Luther Black, David Mitchell, David McCombs, George W. Rickard, A.J. Rickard and Sarah A. Streeter.

The next month, James M. Wells, a special examiner for the Commissioner of Pensions, had investigated the case, and recommended that the pension application again be rejected.

Wells took further testimony in June 1890, but was greatly dismayed at what he heard. He accused William of having "drummed up testimony of questionable character to such an extent that his bare-faced and determined attempt to secure a fraudulent pension has led some of the most reputable citizens of Wood Co., O., to request me to take further testimony in the case. I have done so, and I submit herewith the testimony of four men of high character and unquestionable reputation for truth."

Wells then interviewed lawyer Edwin Fuller,

justice of the peace and former probate judge of the county. Fuller knew the

Minerds, and had officiated at the weddings of two of Alpheus' sisters in the

family home. In their discussions, Fuller told Wells that "the testimony as

given" since the rejection of the claim "constituted some of the most

reckless swearing he had ever heard." Wells came to the conclusion that the

family had "evidently combined to work through this fraudulent claim. I recommend the prosecution of William L. Jewell as principal and William

J. Burditt and the father of the soldier as [criminal participants]."

Obituary, 1909

The Jewells filed an appeal in February 1891, and the original rejection was upheld in April 1892 by the Department of the Interior.

Again greatly dismayed, the Jewells pressed their case again. They asked lawyer George Lemon to see that a someone other than Wells be assigned to the case. "We have no use for him," William wrote. Lemon filed a motion for reconsideration in January 1893, citing inconsistencies in the government's position.

Alpheus vanished again in late 1893. The Bowling Green Daily Sentinel-Tribune edition f of Jan. 2, 1894 said that William "had gone to Lima to see if the remains of a man found dead there were those of Alpheus Minerd, a ward of his, who is somewhat demented. Mr. Jewell found they were not, and to-day called to tell us that Minerd returned home a few days ago and yeteerday again disappeared. Mr. Minerd would like to hear from him."

Unfortunately for the Jewells, their motion was overruled in March 1894. However, for reasons that are not clear, Alpheus did receive some level of pension at the time of his grisly murder in 1903.

In December 1900, William filed an expense account with the Wood County Orphans Court. He acknowledged the receipt of quarterly pension payments of $36 each during the year.

~ The Rest of Their Story ~

The turn of the 20th century brought further

heartache. Alpheus left the Jewell home for the last time in about 1901. Then,

two years later, in July 1903, his "dead and mutilated body" was discovered

a few miles from Kenton, Hardin County, OH. The suspect, a mulatto whom

officials knew ran a petty-theft gang, tracked "his trail through Delaware to

Washington Court House, then to Greenfield and from there to the hamlet of

Carmel." Nichols was arrested, and Alpheus' watch was found in his

possession.

Union Hill Cemetery

The Jewells learned of the murder by reading it in the newspaper. Said the Daily Sentinel, "They at once went to Kenton and asked the privilege of bringing the [home] for burial, but this was denied them because of the condition of the body." Thus ended their saga which had begun some 4 decades earlier.

One can only imagine their emotions when, in 1904, murderer Nichols was executed in the electric chair in Columbus, OH, one of the first individuals to be so put to death in the state.

On Dec. 29, 1904, Pera apparently was residing in Portage, OH, and received an invitation from her sister Jemima Burditt to return to Tontogany for a visit. Pera wrote back, saying:

It's so cold that we would almost freeze to drive down and I can't walk down from Tontogany. I havn't bin well for some time. Last week I took three kines of medison. This week two kines but am getting better and would come down if it wasen't so cold and if Father don't get better I will come enaway.

The day she wrote the letter, Pera's aged

father passed away. She or her sons somehow drove a horse and buggy to Haskins,

Wood County to bring her niece Addie (Benn)

Custer-Cain to the funeral, but Addie's baby was sick, and they could not

make the trip.

Pera's funeral wreath

William passed away on Jan. 16, 1909, following a year's illness. He and Pera are buried at Union Hill Cemetery in Plain Township, Wood County. A large headstone marks their final resting place.

Pera outlived him by 11 years, dying on Feb. 21, 1920. As a remembrance of the funeral, a photograph card was produced at a Bowling Green studio. It shows a beautiful wreath of flowers encircling a small portrait photo of Pera. The image is typical of a funeral practice common in that era that is not often used today.

Copyright © 2002, 2007, 2010, 2022-2023 Mark A. Miner